Osamu Okuda

KLEE GOES TO HOLLYWOOD - CLIFFORD ODETS AND HIS FAVORIT ARTISTS

Summary

It’s fairly well known that American dramatist and scriptwriter Clifford Odets (1906-1963) collected many artworks by Paul Klee shortly after World War II. A photograph taken in 1951 showing Odets in his study next to a wall covered with closely hung Klee works offers particularly important historical documentation of the reception that Klee’s works received in the United States and has often appeared in essays and catalogues focusing on that theme However, very little research has been conducted on how Odets built his Klee collection or what specific works it included. In fall of last year, I started investigating the many unknown aspects of Odets’ Klee collection as part of an editing project for a digital edition of Klee’s oeuvre. In the process, I began to feel it was necessary not just to reconstruct Odets’ collection, but to understand it in terms of his work as a dramatist and the historical conditions in which he lived. This article is an interim report on the progress I’ve made thus far.

![fig. 1 Paul Klee, harte Pflanzen [Hard Plants], 1934, 212 , oil and watercolour on cardboard, 41,2 x 55,2 cm, The Minneapolis Institute of Arts, Gift of Mr. und Mrs. Donald Winston, © The Minneapolis Institute of Arts](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/547344abe4b03e7d0378a6bd/1507817504135-MAKEHRDE0EC27R1YH6FX/Abb+01.jpg)

![fig. 3 Paul Klee, violett-gelber Schicksalsklang mit den beiden Kugeln [Violet-Yellow Sound of Fate with the Two Spheres], 1916, 10, pen and watercolour on paper on cardboard, 17/17,3 x 24,3 cm , The Miyagi Museum of Art, Sendai, © The Miyagi Muse](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/547344abe4b03e7d0378a6bd/1507817504536-Z3RO7O3SEH73J4EBUBRW/Abb+03.jpg)

![fig. 4 Paul Klee, Fata morgana zur See [Fata Morgana at Sea], 1918, 12, watercolour and pen on paper on cardboard, 12,7 x 14,9 cm , San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Extended loan and promised gift of the Carl Djerassi Art Trust I, © San Franci](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/547344abe4b03e7d0378a6bd/1507817506352-08THQ2EBMPLEFDXONWLX/Abb+04.jpg)

![fig. 5 Paul Klee, Fest auf dem Wasser [Water Festival], 1917, 136, watercolour and pencil on paper on cardboard, 20,5 x 24,5 cm, Location unknown, ©Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern, Bildarchiv](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/547344abe4b03e7d0378a6bd/1507817512072-YD193DW3I7DJWK4A2V8G/Abb+05.jpg)

![fig. 6 Paul Klee, bunte Menschen [Colourful People], 1914, 52, Aquarell auf Papier, 13.8 x 20.4 cm, Location unknown, Photo by Adolf Studly (?), ©Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern, Bildarchiv](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/547344abe4b03e7d0378a6bd/1507817510639-YMJW0XSUMUR4KNJMEXJ4/Abb+06.jpg)

![fig. 8 Paul Klee, Stadt im Zwischenreich [City in the Intermediate Realm], 1921, 25, oil transfer drawing and watercolour on paper on cardboard, 31,3 x 48 cm, Columbus Museum of Art, Sirak Collection, © Columbus Museum of Art](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/547344abe4b03e7d0378a6bd/1507817514258-KZ04YBETV2JPN2D23OC6/Abb+08.jpg)

![fig. 12 Erwartender [Expectant Man] , 1934, 150, OK: „Aquarell= Kleister= und Ölfarben / ital Ingres“, Location unknown, Photo: Will Grohmann Archiv, Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, ©Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern, Bildarchiv](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/547344abe4b03e7d0378a6bd/1507817521350-KTL8FHYAA1ABJGOPKNL0/Abb+12.jpg)

![fig. 13 Paul Klee, kl. Dünenbild [Small Dune Picture], 1926, 115, Ölfarbe auf Grundierung auf Karton; originale Rahmenleisten, 32,4 x 23,2 cm, The Menil Collection, Houston, © The Menil Collection, Houston](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/547344abe4b03e7d0378a6bd/1507817521353-7RF1W020EDTD4MQGIX38/Abb+13.jpg)

![fig. 15 Paul Klee, Blick in das Fruchtland [View into the Fertile Country] , 1932, 189, oil on cardboard, 48,7 x 34,7 cm, © Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/547344abe4b03e7d0378a6bd/1507817524813-D425B8J7BU2H9PSD7WLP/Abb+15.jpg)

![fig. 18 Paul Klee, ein Weib für Götter [A Woman for Gods], 1938, 452, Kleisterfarbe und Aquarell auf Papier auf Karton, 44,3 x 60,5 cm , Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler, © Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/547344abe4b03e7d0378a6bd/1507817530696-0B9JVRYIHVYJU3VGJOOB/Abb+18.jpg)

![fig. 20 Paul Klee, Blumengärten von Taora [Flower Gardens of Taora], 1918, 77 , Aquarell auf Grundierung auf Papier auf Karton : a) 16 x 11,3 cm b) 15,9 x 13,3 cm , Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College, Oberlin, © Allen Memorial Art Museum,](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/547344abe4b03e7d0378a6bd/1507817533945-G1YS4PSQCF9FB9R23OD0/Abb+20.jpg)

![fig. 21 Paul Klee, irrende Seele I [Wandering Soul I], 1934, 162, Ritzzeichnung in Wachsgrund auf Papier auf Karton, 18 x 26 cm . The Hugh Lane Municipal Gallery of Modern Art, Dublin, Vermächtnis Charles Bewley, © The Hugh Lane Municipal Gallery](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/547344abe4b03e7d0378a6bd/1507817534326-24QISDJNKNF8SGRKHX5E/Abb+21.jpg)

![fig. 22 Paul Klee, panisch-süsser Morgen [panicky-sweet Morning], 1934, 11, coloured paste and watercolour on paper on cardboard, 31 x 49 cm, Private collection, USA, ©Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern, Bildarchiv](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/547344abe4b03e7d0378a6bd/1507817536671-7E0LNBESITTZYFHWTGW9/Abb+22.jpg)

1. Prologue

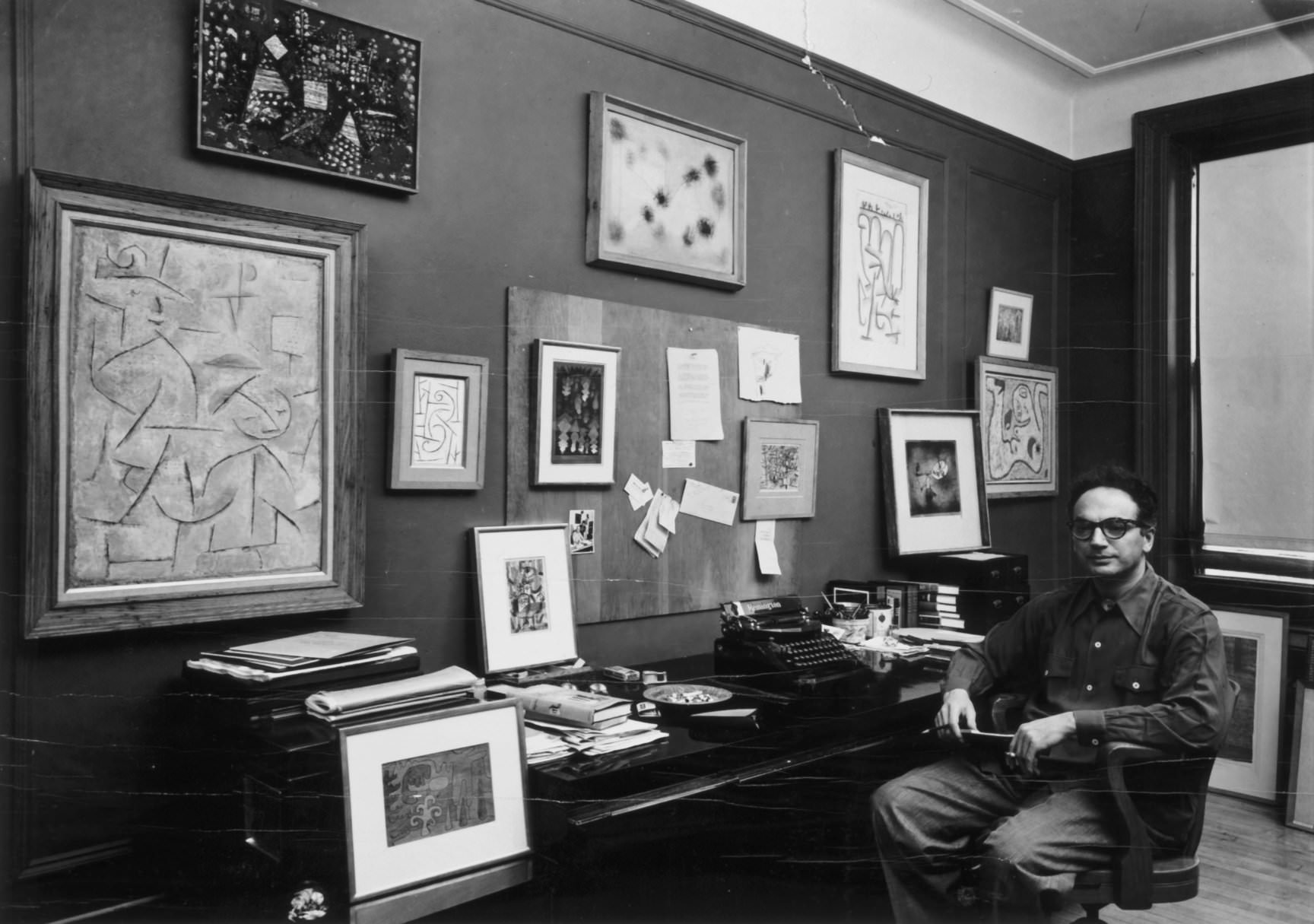

It’s fairly well known that American dramatist and scriptwriter Clifford Odets (1906-1963) collected many artworks by Paul Klee shortly after World War II. A photograph taken in 1951 showing Odets in his study next to a wall covered with closely hung Klee works offers particularly important historical documentation of the reception that Klee’s works received in the United States and has often appeared in essays and catalogues focusing on that theme (fig. 17). However, very little research has been conducted on how Odets built his Klee collection or what specific works it included. Odets is recognized as one of the most important American dramatists of the first half of the 20th century. His friend, the actor Marlon Brando, once commented that “To me, he was the thirties.”1 This pithy assessment reflects Odets’ stature as a new playwright at the Group Theatre during the Great Depression, who wrote many hit plays performed in quick succession that had a leftist political viewpoint. Becoming well established in his career before the age of 30, he was nicknamed the “Bernard Shaw of the Bronx” and was truly the darling of the age. Later, in the 1940s and ‘50s, he left political themes behind and focused instead on various aspects of the American Dream as seen from a personal point of view, but he never again achieved the kind of celebrity he enjoyed in the ‘30s. What is fascinating from our point of view, however, is that Odets began collecting artworks, especially those by Klee, just after the war in the mid-1940s, when Communism was perceived as an enemy ideology and American society was roiled by the possibility that scriptwriters, actors and film directors in Hollywood where Odets worked were card-carrying Communists. Of course, as a professional scriptwriter himself, Odets had ample income, which was probably the first condition that an art collector had to meet. Another important factor was the fact that Odets became acquainted with the art dealer J.B. Neumann (full name Jsrael Ber Neumann, 1887-1961) who made Klee paintings available for a relatively low price. Neumann had moved to New York from Berlin in 1923 and opened a gallery; he was a pioneer in introducing Americans to modern German art. Odets was therefore able to learn from him about Klee and other members of the European avant garde and receive advice. Odets moreover dabbled in painting himself. Although his works were influenced by Klee, he also developed a variety of original styles2 and had two solo exhibitions at Neumann’s gallery. In fall of last year, I started investigating the many unknown aspects of Odets’ Klee collection as part of an editing project for a digital edition of Klee’s oeuvre. In the process, I began to feel it was necessary not just to reconstruct Odets’ collection, but to understand it in terms of his work as a dramatist and the historical conditions in which he lived. Of course, my research has not progressed to the point where I can fully explicate these issues. This article is therefore an interim report on the progress I’ve made thus far.

2. Odets and Neumann

Odets met the art dealer J.B. Neumann in 1940. Odets was with stage designer Boris Aronson, doing preparatory work on Odet’s play Clash by Night. They were visiting Staten Island in New York Harbor, where the play is set.3 Though the focus of the story was a tragic love triangle, the play indirectly reflected Odet’s antiwar sentiments. Premiering as it did shortly after Japanese forces attacked the U.S. Navy at Pearl Harbor in December 1941 (marking the beginning of America’s participation in the Pacific War), the play ended in failure. In any case Aronson, a native of Kiev, had immigrated to the U.S. in 1923, the same year as Neumann, and enjoyed initial success as a stage designer influenced by Russian Constructivism. Beginning in the mid-1930s, however, he also began creating traditional, realistic stage designs. In 1935, he was the stage designer for Odets’ Awake and Sing!, which was performed by the Group Theatre. Aronson was also active as a painter and had participated in an exhibition organized by Neumann. It seems plausible that Aronson had invited his friend Neumann along on the Staten Island trip with Odets. In his youth before becoming an art dealer, Neumann had aspirations of becoming a stage actor and attempted to study at the Max Reinhardt Seminar in Berlin, but his inability to conquer his stage fright forced him to quit.4 It’s also worth noting that Odets was not without connection to Reinhardt himself, having been deeply impressed by a production of the play The Miracle staged by Reinhardt on Broadway in 1924. Also, Odet’s second wife Luise Rainer, whom he married in 1937, had until 1935 performed at the Theater in der Josefstadt in Vienna, where Reinhardt had been the intendant. Neumann’s interest in theater and performance was evident after he became an art dealer in the projects he planned for his galleries. His first foray was in Berlin in January 1918 at his gallery Graphisches Kabinett, where he hosted Richard Huelsenbeck’s famous “First Dada Lecture in Germany.” After immigrating to New York, Neumann continued to include lectures, concerts and performances in his gallery programs. He was particularly fond of the plays of Bertolt Brecht, and was an opera lover as well; as mentioned in his personal notes, he frequently attended performances of such works as Mozart’s Don Giovanni and The Marriage of Figaro, and Richard Strauss’ Der Rosenkavalier.5 For his part, Odets was no less an enthusiastic music aficionado than Neumann; in 1924 he became “America’s first disc jockey” by hosting a radio show on WBNY that featured classical and modern music combined with improvised narration.6 In his critical biography of composer Aaron Copland, who was Odets’ friend, the musicologist Howard Pollack mentions Odets’ obsession with music:

“Odets was passionate about music. He loved Mozart, Schubert, and especially Beethoven, in whom he saw, in earlier years at least, a prefigurement of communism. He became good friends not only with Copland but with Hanns Eisler, with whom he collaborated on a number of projects. He amassed a large records collection of old and new works […]. Odets especially admired Copland’s music, and in 1939, flush from the success of Golden Boy, he agreed to commission the Piano Sonata (1941), which was dedicated to him, for $500. […] In the early 1950s, he attempted to interest Copland in writing another piano sonata or a string quartet in exchange for a Klee that he owned.”7

Viewed in this way, one can understand how Odets and Neumann shared similar interests and cultural backgrounds despite the nearly 20-year difference in their ages. Of course another unifying factor we can’t overlook is their shared Jewish heritage rooted in Russia and Eastern Europe, but it was works of art, particularly those of Klee, that tangibly deepened their friendship.

As early as 1921, Neumann had already organized a Klee exhibit in this Graphisches Kabinett gallery in Berlin. After relocating to the United States, he wrote a letter to Klee saying how, from 1930 on, he had fallen increasingly in love with Klee’s work and had begun working to disseminate it in America.8 The first fruit of those efforts was a Klee show mounted in the New York Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 1930. Neumann had originally planned to hold the exhibit in his own gallery, but lack of space prompted him to move the project to the museum.9 In 1939, Neumann held a solo exhibition of Klee’s work in collaboration with Marian Guthrie Willard. Between the reopening of his New Art Circle gallery the following year and 1952, Neumann organized five solo shows featuring Klee. Correspondence between Neumann and painter Max Beckmann have recently been edited, throwing new light on their friendship,10 but no comparable study has been done on the relationship between Neumann and Klee. I have begun to collect materials concerning that relationship as part of a project to organize all of Klee’s works in a digital edition.

3. Odets’ Klee Collection

Odets first visited Neumann’s New Art Circle gallery in November 1940, when he bought paintings by Maurice Utrillo and Marcel Gromaire. Concerning the Utrillo, he noted the following in his diary: “A painting of charming quality, a snow scene, a street, a typical Utrillo but an excellent one from his so-called white period.”11 From this we can perceive that Odets had a delicate sensibility that preferred art with depth over gaudy display.

It wasn’t until after World War II, however, that Odets purchased his first Klee work. In 1943, he cut his ties with Broadway and moved to Hollywood, where he made a fresh start working as scriptwriter and director of the film None but the Lonely Heart. Although that film, which featured Cary Grant and Ethel Barrymore, could hardly be called a smashing success, Barrymore did win an Oscar for Best Actress in a Supporting Role, Grant was nominated for Best Actor, and composer Hanns Eisler was nominated for Best Music. In 1946, Odets wrote the screenplays for the film noir Deadline at Dawn and the comedy Humoresque. The latter in particular proved popular, ranking 46th in box office receipts for 1947.

This was the period when Odets began to get serious about collecting works by Klee. Choosing not to deal exclusively with Neumann, he also bought paintings from Neumann’s competitors, including Curt Valentin of Bucholz gallery (renamed Curt Valentin Gallery in 1948); the Nierendorf gallery (both in New York City), and the Rosengart Collection in Lucerne, Switzerland. In many cases, the precise route of acquisition is unknown. Also, it’s unclear at this time just how many works were acquired with Neumann acting as intermediary. Leaving such matters to future provenance research, I’ll focus here on discussing what Odets said about his own activity as a Klee collector and explore some related psychological aspects.

According to Odets himself, the first Klee he purchased was harte Pflanzen [Hard plants] 1934, 212.12 (fig. 1) This work, like Klee’s tableau Kind und Tante [Child and aunt] 1937, 149, was purchased in the spring or early summer of 1946 from the Klee Gesellschaft in Bern through the Nierendorf gallery,13 with Neumann acting as Odets’ agent. It was sent from New York to Odets’ home in Los Angeles in June of that year.14 It seems that harte Pflanzen opened Odets’ eyes to Klee, as reported by art critic Henry McBride: “Mr. Odets’ first purchase, he told me, was a whimsy that struck him lyrically, with a strain of pure Debussy in it, and having been won in this fashion, he quickly ran the whole Klee gamut…”.15

This quote underlines Odets’ refined sensibility, which was already intimated by his acquisition of the Utrillo, as we’ve seen. In addition, however, it’s fascinating to note the point of contact with music that Odets shared with Klee. Odets “heard” a Debussy melody in harte Pflanzen and immediately set about exploring all of the tonalities found in Klee’s art. In a letter from an unknown sender received by Odets in June 1946, a list was enclosed detailing the works in Odets’ art collection that were sent from New York to his Los Angeles home. It’s not surprising to discover a total of 29 works by Klee on the list.16 In a letter sent to Neumann a year later, dated June 23, 1947, Odets writes, “I have spent almost $40,000 on Klees in the past 14 months.”17 In a letter written to the Nierendorf gallery in July 1947, Odets writes that his Klee collection at that point had grown to 55 works.18 Looking back on 14 months of feverish collection, Odets had this to say in a letter dated June 14, 1947:

“Time will have to get between me and the purchases before I am alone with them, for it is a great sacrifice for me to spend as much money on pictures as I’ve been doing this past year […]. Bless this saint: He goes in my heart with Rembrandt, Goya, Daumier, Mozart, Schubert, Heine, Cezanne and several other ‘failures.’ The whole church has only a few saints to equal them. I sit and make my own saints.”19

In autumn of 1947, Odets’ collection fever apparently broke when the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) in the U.S. Congress began investigating communist activities in Hollywood. He became embroiled both directly and indirectly in the government’s anti-Communism campaign, and also had to deal with matters at home, including his children’s education. In 1948 he began selling off some of his art collection, and it seems he also engaged in art exchanges. But he never stopped collecting Klee works altogether. We can surmise this because of Henry McBride’s 1951 article in Art News that I quoted above, where McBride states that Odets’ Klee collection was comprised of 60 or more works at that point in time.20 The astonishing variety found in the collection gives one the impression that Odets selected his purchases with the conscious intention of showcasing Klee’s many artistic styles and the diversity of his themes. The inclusion of many pictures associated with the theater and opera might well reflect the main vocation of the collector, but it also might indicate the role played by Neumann as agent.

4. Research Results Based on New Materials

According to the 9-volume Catalogue raisonné Paul Klee that was published from 1996 through 2004, a total of 70 Klee works were included in Odets’ collection at one time or another. This conclusion was of course based on an examination of all the research materials that were available at the time. The re-examination currently underway, however, has clarified the following: 1) Two works listed in the catalog in fact had no connection with Odets at all (1929, 183; 1933, 293); 2) Five additional listed works might not have had a connection with Odets either, but further research is needed to be certain (1911, 60; 1919, 67; 1920, 37; 1925, 248; 1934, 24); and 3) Twelve previously unlisted works (including two lithographs) were in Odets’ collection. (See the appended list)

In pursuing the current research project, I have re-examined materials that were previously consulted and focused on the following new documents in an attempt to make further progress in reconstructing Odets’ Klee collection.

a. Photograph of Odets taken on August 1, 1946 for publication in the New York Post.

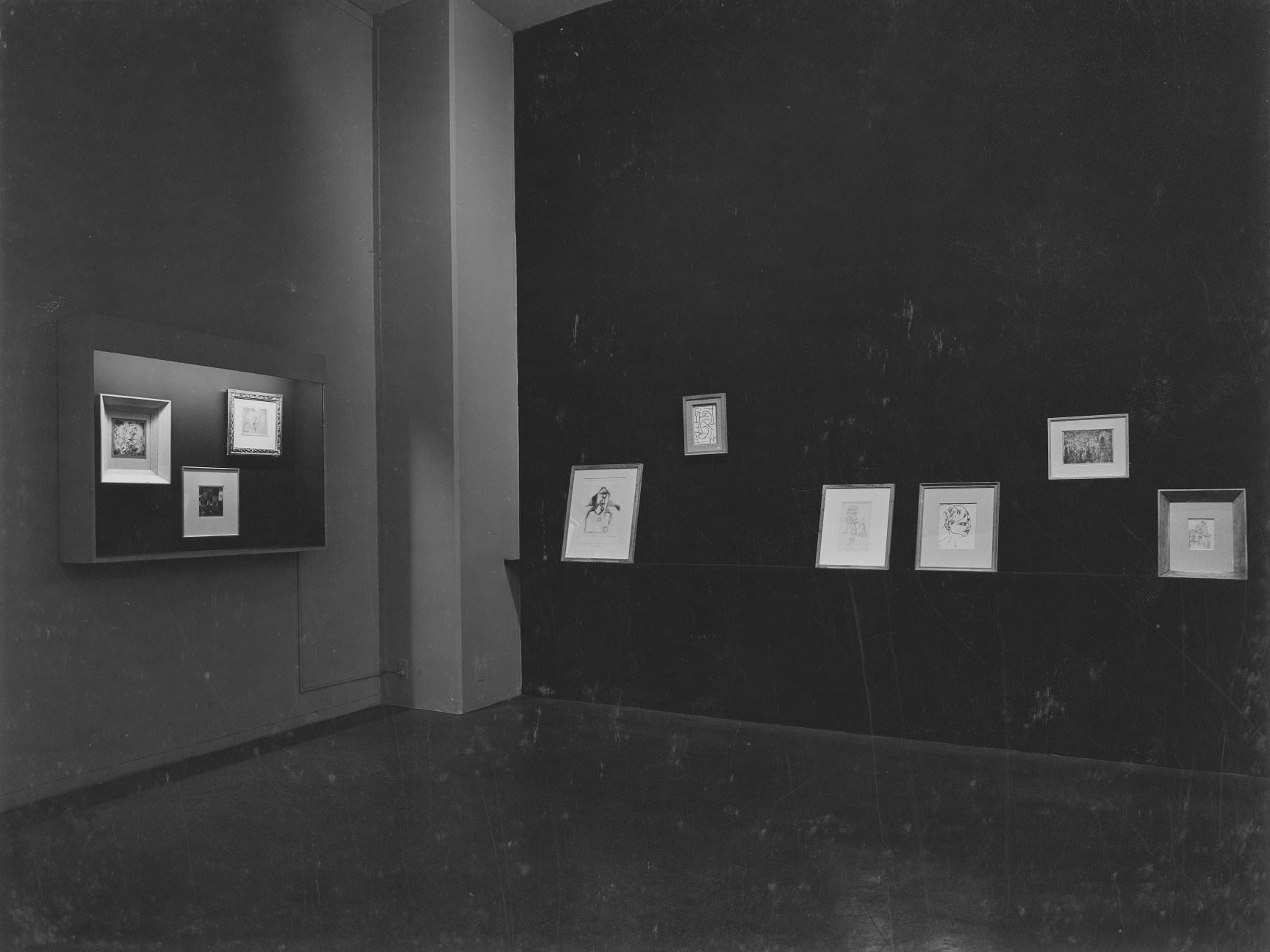

b. Checklist and venue photograph from Selections from 5 New York Private Collections, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, June 26-Sept. 9, 1951.

c. Photograph of Odets in his study taken for an article in Art News written on the occasion of the exhibition cited in b. above.

d. Catalog published for an exhibition held in 1952 at the Farnsworth Museum, Wellesley College and a list compiled by Curt Valentin titled “Paintings by Paul Klee: Clifford Odets Collection.”

a. Photograph of Odets taken on August 1, 1946 for publication in the New York Post

This photo, taken by Anthony Calvacca, lay hidden in the archives of the New York Post until recently made available to the general public by Getty Images (fig 2). Odets is shown sitting in front of his typewriter in a workroom, probably in his house in Los Angeles. He’s looking at a sheet of paper above the typewriter, which has on its reverse side a picture that can’t be clearly made out. Colored pencils in the lower left foreground and paintbrushes in the background behind them seem to indicate that Odets also used this room as a studio for his work as an amateur artist. Odets held his first solo exhibition at Neumann’s New Art Circle gallery in New York in January 1948; it was covered in Art News, which mentioned 30 “gay little primitivist watercolors”21 that were “already above the hobby level.”22 What interests us here however are the four artworks shown hanging on the wall behind Odets in the photo. Three of them are listed in Catalogue raisonné Paul Klee as being in Odets’ collection and therefore fairly easy to identify as described below.

Lower left: violett-gelber Schicksalsklang mit den beiden Kugein [Violet-yellow sound of fate with the two spheres] 1916, 10 (fig. 3).

Upper right: Fata morgana zur See [Fata morgana at sea] 1918, 12 (fig. 4)

Lower right: Fest auf dem Wasser [Water festival] 1917, 136 (fig. 5)

These three works were all included in the list of artworks sent from New York to Los Angeles that I already mentioned. This is consistent with the fact that the photo was taken in August 1946, shortly after the works were sent.

The fourth artwork, shown at upper left on the wall, cannot be confidently identified even after consulting the Catalogue raisonné Paul Klee. Upon closer inspection, though, we can see that it is the watercolor that I surmised to be bunte Menschen [Colourful People] 1914, 52 in an essay I published in 2007 titled “The Image as Stage: Paul Klee and the Creation of Theatrical Space” (fig. 6). Klee had traveled to Tunisia in April 1914, and upon his return to Munich he worked as the set designer for a production of Euripides’ Bacchae produced by Hugo Bal. It’s my hypothesis that bunte Menschen was connected to that project. I invite my current readers to read my 2007 essay (see appended pdf), while noting here that this is new evidence regarding the relationship between the picture and Odets. Of all the works cited in the above list, the only title that can be thought to match this work is called Circus Scene. A list later compiled by Curt Valentin of Odets’ Klee collection lists as number 8 a watercolor with the similar title Circus Folk, which Valentin further notes is “Clifford’s title.”23 The whereabouts of bunte Menschen became uncertain after it was exhibited at the Kestnergesellschaft in Hanover, Germany in 1921, because neither the work itself nor its mounting bore the year, work number, or title, making identification difficult. Looking at the picture in the 1946 photo, we can see that the mounting between the picture itself and the frame is black and has no identifying information on it; this probably explains why Odets gave the picture his own title of Circus Folk. When the picture was appraised in 1989 by the Paul Klee Foundation at the Kunstmuseum Bern, Switzerland, it was judged to be authentic but was not identified. At that time the mounting was covered in blue paint, which was also difficult to identify (fig. 7). The blue paint was probably applied when the picture entered the collection of G. David Thompson of Pittsburgh after Odets’ death.24

As the 1946 photo shows, violett-gelber Shicksalsklang mit den beiden Kugeln [Violet-yellow sound of fate with the two spheres] 1916, 10 hung below bunte Menschen on Odets’ wall. Depending on how one looks at it, it could also evoke the performance of an opera or circus. This watercolor is included in a catalog of the holdings of Museum Folkwang in Essen, Germany published in 1929, where it was given the title Fantastische Gottheit.25 A literal English translation of that title (“Fantastic goddess”) is included in the list of works shipped to Odets in Los Angeles in June 1946. One can find a smattering of other Klee works showing theatrical scenes in Odets’ Klee collection, and it’s natural to wonder if Odets drew inspiration from them for the scene settings and stage designs in his own work as a dramatist. A lack of materials makes it impossible to answer this question at this time, but a hint as to where further investigation might be directed is found in this anecdote transmitted by Lee Strasberg, the famous theater educator who was one of the founders of the Group Theatre:

“While teaching a director’s unit at the American Theater wing, someone brought in an offbeat play, and I tried to describe to the student the way the director must get a vision of the set and build a world for this play. Later, I was at Clifford Odets’ apartment and on the floor was a Paul Klee painting called Between Heaven and Earth. The quality I was trying to describe to the student was in the world that Klee created. Odets collected Klee and saw him as a great artist. I tried to appreciate him but never could until then. It seemed like magic and I was stirred by it.”26

The painting Strasberg calls Between Heaven and Earth was probably Stadt im Zwischenreich [City in the intermediate realm] 1921, 25 (fig. 8), which Klee painted in 1921. It was first publicly exhibited in the United States at MoMA in 1951, as described below.

b. A checklist and venue photograph from Selections from 5 New York Private Collections, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, June 26-Sept. 9, 1951.

In 1951, MoMA held a special summer exhibition showcasing local, privately owned art collections. Eighty-seven works owned by Rockefeller, Whitney, Senior, Colin and Odets were selected for display, all examples of modern art from Europe and the United States featuring artists ranging from Toulouse-Lautrec to Rothko. Twenty-four works were selected from Odets’ Klee collection, but what merits special mention is the fact that Klee’s small-scale works were exhibited (though admittedly in a different section) with great works by such Abstract Expressionists as Robert Motherwell, Bradley Tomlin, Marc Rothko, Jackson Pollock and William Baziotes, who were all heavily influenced by Klee. Because no catalog was made for the exhibition, the exhibit was not included in the ZPK (Zentrum Paul Klee) databank until photos of the venue, a checklist and a press release were posted on MoMA’s homepage.27 Those items have proven to be extremely important for my own research on Odets’ Klee collection (Abb. 9), (Abb. 10) Of particular value is the information that two works were displayed that had previously not been considered part of Odets’ collection, of which one is referenced in the checklist, making identification possible for the first time. That work is Erwartender [Expectant man] 1934, 150, which was painted in 1934. It is displayed second from the right in a corner of the exhibition venue labeled “Mr. and Mrs. Clifford Odets” (fig. 11).

b1 Ewartender [Expectant man]

Of the 24 works that appear on the checklist of Odets’ Klee Collection, only 51.829, Expectation, appears to match the photograph. The ZPK has photographic data of this picture, but a lack of information kept it from being identified. In the Catalogue raisonné Paul Klee, it’s designated as Ohne Titel [Untitled] and included as the last work of 193428 (fig. 12).

Erwartender was displayed in a Klee exhibition held at Kunsthalle Basel in Switzerland in 1935. Priced at 700 Swiss francs, it failed to sell. Three years later at the Galerie Roland Balaÿ et Louis Carré in Paris, it was again displayed in an exhibition called “Paul Klee: Tableaux et aquarelles de 1917 à 1937” and was given the French title Dans l’Attente. After the death of Klee and his wife Lily, the painting became part of the Klee Gesellschaft collection and was probably entrusted to the art dealer Kahnweiler on consignment in the first half of 1947. Curt Valentin was traveling through Europe buying Klee artworks that year; sometime around June he wrote a letter to Odets from Paris where he lists seven works that he had purchased, which included Dans l’Attente.29 In another letter dated September 16 of that year and typed on stationary with a Buchholz Gallery: Curt Valentin letterhead, he writes, “I made a mistake in my list yesterday: Number 8403, ‘Dans l’Attente’, is not Frs. 120,000 but Frs. 84,000.”30 It seems quite certain that Erwartender entered Odets’ collection no later than June 1951. When it was displayed at the Saidenberg Gallery in New York with the title The Child who Waits in a Klee show held in spring of 1954, the catalog did not state that the painting was part of Odets’ personal collection. This seems to indicate that Odets either sold Erwartender to Saidenberg or exchanged it for another work before that exhibition was held.

It’s my conjecture that Odets was charmed by the image of a young man who seems to be either lost in a dream vision or standing stupefied with amazement, especially when coupled with the French title Dans l’Attente [While waiting]. There can be no doubt that the title naturally reminded him of his hit play of 1935 Waiting for Lefty. That work, which centers on a taxi driver strike during the Great Depression, has a protagonist named Lefty, the chairman of the strike committee, who never appears on stage because he’s already been killed. While Lefty symbolizes revolution and socialism, his absence also sounds a warning bell that he is nothing more than an empty ideal. By focusing attention on an offstage character for whom other characters wait, Odets expands the time and space of the drama in a way that arguably prefigures Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot. Furthermore, Waiting for Lefty is supported by the world created in Erwartender, in which a person depicted seems trapped in a confining space, thereby psychologically broadening the imaginative dimension of viewers by directing it outside the picture itself. In the MoMa exhibition held in 1951, Erwartender was paired with Vogelfänger [Bird catcher] 1930, 47, which brings to mind the character Papageno in Mozart’s opera, The Magic Flute. This choice was probably made with the dramatic qualities of both pictures in mind.

b2 kl. Dünenbild [Small Dune Picture]

On the same wall as Erwartender [Expectant man] and Vogelfänger [Bird catcher] at the MoMa exhibition, two other pictures are displayed that are about the same size as the others and in almost identical framing: schwarzer Fürst [Black prince] 1927, 24 and kl. Dünenbild [Small dune picture] 1926, 115. Both are now relatively well known, but strangely, the latter is not listed as part of Odets’ old collection in the Catalogue raisonné Paul Klee (fig 13). This painting, with the English title Little Dune Picture, had already been in a large show that toured San Francisco, Portland, Detroit, St. Louis, New York, Washington, D.C., and Cincinnati from March 24, 1949 through May 24, 1950. The catalog for that exhibition cites it as having been “Lent by Mr. and Mrs. Clifford Odets, New York.”31

kl. Dünenbild [Small dune picture] was included in the previously mentioned list that was sent with a letter to Odets in Los Angeles in June 1946, where it was titled Little Landscape of the Dunes, indicating that Odets had it in his collection at least from that time.32 But why did Odets purchase this landscape? Could it be because, as with harte Pflanzen [Hard Plants], the first Klee work he collected, Odets was captivated by the colorful linear arabesques so reminiscent of music? It’s fascinating to note that Odets himself painted a water color titled Winter Scene in 1952 that can be compared with the Klee work and is even more musically evocative with its incorporation of images suggesting a musical staff (fig 14). In his use of thin, overlapped layers of watercolor paint and bundled, parallel lines, Odets seems to have referenced other Klee works, as well. His special interest in the structural composition of Klee’s landscapes is evident in his Sea, rocks and clouds already painted in 1949, which he closely modeled on Klee’s Blick in das Fruchtland [View into the fertile country] 1932, 189 (Abb. 15), (Abb. 16) . It’s not yet clear when Odets acquired Blick in das Fruchtland, but if he did indeed use it as a model for his own painting, it must have been in 1949 or earlier. Like the Klee, the lower half of Odets’ painting depicts the beach and rocks in a tightly knit composition while the sky opening above is full of his own freely painted fantasy. The contrast between the upper and lower halves extends to the way the paint is applied. The blue of the sky in particular has a nuanced expressiveness that shows that Odets had mastered a refined watercolor technique acquired through self-study.

c. A photograph of Odets in his study taken in 1951 for an article in Art News written on the occasion of the exhibition cited in b. above.

When the above-mentioned Selections from 5 New York Private Collections was held at MoMA in 1951, art critic Henry McBride visited the contributing collectors and wrote an article about them titled “Rockefeller, Whitney, Senior, Odets, Colin” in Art News. A photo of Odets in his study taken by Aaron Siskind accompanied the article (fig. 17). As I noted at the beginning of this article, this photo was often used in catalogs and magazines to symbolize Klee’s reception in the United States after World War II and later. Until now, however, no research has been done specifically on the Klee pictures that are shown on the wall. In trying to identify the pictures, I’ve been able ascertain the following two works that were previously thought to have no connection with Odets’ Klee collection.

ein Weib für Götter [A woman for gods] 1938, 452

botanischer Garten (Abteilung exotische Bäume) [Botanical garden (exotic tree section)] 1939, 100

Here, I’d like to focus on ein Weib für Götter [A woman for gods] (fig. 18). Today it’s a famous work, and it’s a bit surprising that no one noticed for many years that it had once been part of Odets’ collection. A tableau, it was never displayed in an exhibition during Klee’s lifetime. It’s public debut was in a Klee show in 1944 in the 2nd Floor Galleries of the Philadelphia Art Alliance, where it appeared with the English title Bride of the Gods. The catalog for that exhibition notes that the work was “Lent by Nierendorf Gallery, New York.”33 It is also included with the same title in the list of items sent to Odets in Los Angeles in June 1946 that I’ve already frequently referenced. Odets probably did not acquire the picture directly from Nierendorf Gallery but rather through Curt Valentin.

The first person to publish commentary on ein Weib für Götter was an art historian named Max Huggler. He organized a large retrospective of Klee’s work at the Kunsthalle in Bern in 1935, and subsequently acquired a deep knowledge of the artist’s oeuvre, especially the later works. In a seminal book titled Paul Klee: Die Malerei als Blick in den Kosmos [Paul Klee: Painting as gazing at the universe] published in 1969, Huggler makes the following observation: “A Woman for Gods fills the canvas area in an admirable invention: the two feet are braced on the edge of the upper corners, and the reclining, outstretched body connects a floating existence with supporting force. The sun wheel and a mouth inside the womb are evidence of cosmic content.”34

Interestingly, Odets appears to have applied the deformed body of the Klee work in his own watercolor Crime of Passion, which is dated June 1947 (fig. 19). However, he takes the mythic, cosmic dimensions of Klee’s painting and relocates them in the ordinary human world, making the woman a victim not of the gods but of a criminal. This brings to mind the tragic love triangle of whirling passions depicted in Odets’ play Clash by Night, which premiered in 1941. In this case, Klee’s work might have served as an objectification and reflection of Odets’ own creative activity.

d. Other materials

Here I’d like to introduce just three more works by Klee that, as a result of the present investigation, were found to once belong to Odets’ Klee collection.

A Klee show was held in 1952 at the Farnsworth Museum at Wellesley College on the outskirts of Boston, in which eleven Klee works from Odets’ collection were displayed. One of them, Blumengärten von Taora [Garden in Taora] 1918, 77, featured a composition favored by Odets that is reminiscent of a theatrical backdrop. Klee cut his completed watercolor painting vertically and mounted the two halves with a narrow space in between. Using this “cut and paste” method, Klee created a vibrant empty space in his painting (fig. 20). Another work, Barbarische Komposition [Barbarian composition] 1918, 68, which was also in Odets’ collection, was made in the same way, leading to the conjecture that Odets had an interest in this special technique employed by Klee.

In the list Valentin compiled of works in Odets’ Klee collection, there are two more works that had not previously been identified. One of them, number 31 on Valentin’s list, has a German title, Irrende Seele. Klee made two works with this title in 1934, namely irrende Seele I [Wandering soul I] 1934, 162, and irrende Seele II [Wandering soul II] 1934, 166. It was not possible to say with certainty which of these two paintings Valentin was referencing in his list. However, irrende Seele I was shown in a Klee exhibition at Neumann’s New Art Circle in 1952 with the title Straying Soul I, and the catalog for that show contained an image of the work, so it’s almost certain that this was the one in Odets’ collection35 (fig. 21). It was one of the most abstract Klee works that Odets owned. Yvonne Scott suggests the possibility that Klee was influenced in its creation by the Carnac stones of Brittany, particularly the patterns inscribed on the megalithic passage graves in Morbihan.36 Klee actually traveled to Brittany in the summer of 1928 and visited the ruins of the Carnac stones. The fact that he bought specialized books at that time concerning the abstract line drawings on the surfaces of megaliths and their connection to ancient burial culture makes it easy to surmise that he had more than a passing interest.

Going back to Valentin’s list, we find a work titled Street Morning at number 39. This work was also impossible to identify, but was probably panisch-süsser Morgen [Panicky-sweet morning] 1934, 11, which was put up for auction at the Parke-Bernet Galleries in New York in March 1966 and listed in that catalog as once belonged to Odets37 (fig. 22). With the title Panicky Sweet Morning, this same picture was first publicly displayed at a Klee show held at the Art Students’ League Gallery in New York in 1941, and was subsequently displayed at the Curt Valentin Gallery in 1953 and the Saidenberg Gallery in 1954. The Abstract Expressionist painter John Hultberg, who probably saw the exhibit at the Students’ League, later wrote the following recollection: “Paul Klee made the terrifying journey into another person’s consciousness a hilarious, though jittery adventure, a ‘panicky sweet morning.’ He left doors open for us to follow, but few are risking the shoals glimpsed there, flowering orchards of bloody foam.”38

Odets set out as a new art collector in 1940 with the acquisition of an Utrillo. Six or seven years later, he had added such experimental works as Klee’s irrende Seele I and panisch-süsser Morgen to his collection. This implies that Odets was not oblivious to the work of the younger generation of postwar artists. Although no concrete evidence supporting this conjecture has been found, by the 1950s his collection included the work of such Abstract Expressionists as Adolph Gottlieb and William Baziotes,39 indicating that he was sensitive to new movements in the art world that went beyond Klee. This is amply communicated in following excerpt taken from an essay on Willem de Kooning published by Odets in 1961.

“Today, art history moves faster in the United States, perhaps because of the rich man's need for ‘conspicuous consumption’; but certainly, among other reasons (critics like Hess, Greenberg, Meyer Shapiro, et al), because our museums are younger of heart. Having already swallowed whole and spit out such earlier 20th century American pioneers as John Marin, Hartley, Dove, Stuart Davis, Max Weber and such (as if we have really seen them yet!), we are now face to face with such later Americans as Gorky, Pollock, Gottlieb, Rothko, Still and the subject of the present show, Willem de Kooning.”40

5. Epilogue: Odets’ View of Klee

In this final section, I’d like to introduce some comments and the only short essay that Odets wrote about Klee in an attempt to clarify how he regarded Klee’s art.

I’ll start with a fairly succinct description of Klee that Odets wrote in a letter addressed to Neumann:

“When you spread six Klees across a blank white wall you are looking at six works of genius which keep their life intact and full no matter how often seen […] Klee has everything an artist should have except perhaps heroism and that quality he has in the continuity of his work and perhaps mostly at the end and at the very beginning. Heroism needs an ‘against’ and Klee didn’t have that. In certain respects Klee has qualities that do not come together in one man anywhere in the history of art. He has what anonymous and communal arts have had and someday, if care is not taken to make a catalogue, they will accuse Klee of being a school instead of a man.”41

Odets adopts a fascinating perspective when he connects Klee’s art not with individualism but with anonymous and communal arts. It seems certain that Odets was strongly impressed by the anonymous and collective aspects of such Klee works as irrende Seele I [Wandering soul I] that we’ve already examined. But in life Klee was an extremely individualistic artist and was often criticized for that reason, especially by the Constructivists. Klee’s positive reception in the U.S. in the 1930s and 40s was for the most part an affirmation of the individualism of his art.42 This stance was in direct opposition to the persecution of the avant-garde by the Nazis who, lamenting the loss of connection between Kunst (art) and Volk (people), attempted to restore that connection by labeling modern works “degenerate art.” For example, the art critic Clement Greenberg had this to say in an article titled “On Paul Klee” published in the Partisan Review in 1941: “Klee was rather complacent about the privateness of his art qua privateness and strove to accentuate rather than diminish it in his most characteristic productions. Here again he was very much a German, a product of his national culture no less than of his times.”43

Odets did not partake in the opinions of art specialists like Greenberg but rather viewed Klee from his own particular perspective, reflecting the problems he himself confronted as a playwright. In his work after Waiting for Lefty, Odets consistently struggled with the difficult and contradictory problem of winning commercial audiences through art. He incorporated various forms of popular culture in his plays and attempted to fuse stage and audience (that is, art-as-production and mass culture).44 In a sense, Odets seems to have connected his own theatrical ideals with Klee’s works, which became increasingly popular in the United States in the 1930s and 40s.

While it may seem like an unconnected leap, I feel that the final message that Klee shared in a lecture he gave in 1924 at the Kunstverein (the public art gallery) in Jena, Germany is in fact relevant to the paradox that troubled Odets. First published in German in 1945 as “Über die moderne Kunst”, it was published in English with the title “On Modern Art” in 1948.

“Sometimes I dream of a work of really great breadth, ranging through the whole region of element, object, meaning and style. (…)

We must go on seeking it!

We have found parts, but not the whole!

We still lack the ultimate power, for:

The people are not with us.

But we seek a people. We began over there in the Bauhaus. We began there with community to which each one of us gave what he had. More we cannot do.”45

In bringing this interim report to a close, I’ll quote from a short essay titled “The World of Paul Klee” that Odets wrote in 1952 and finally published in Neumann’s gallery bulletin in 1959. The following passage echoes the ideal of a comprehensive art that Klee himself described in his lecture in Jena.

“That Klee's rare constellation of talent, sensibility and genius will group itself again in one man in our time is very doubtful. Draughtsman, painter, poet, musician and thinker, situated as he was in a certain elbow of time, he stands unique in the entire range of art. When one day his personal journals are in print perhaps they will reveal the most cogently thoughtful of ٢٠th century artists. In those books we shall find intellectual reasoning stubbornly wedded to intuition and feeling, modestly linked with the boldness of a lightning flash, lyric and even supernatural insights weighted with middle class good sense, ripe wisdom salted with wit, high sophistication leavened with painful humility, and silent dedication veined with almost wild exuberance. And all of these qualities, of course, are the very qualities we find in Klee's picture world. The subjects, as has been said, range from delightful to fearsome and fantastic. Every article and object of his inner and outer landscape, every change of weather, symbols and creatures of the past, present and future—those seen and unseen! — all are tamed to Klee’s table and respiration; and move with compliant style within his magician’s world.”46

Endnote

- Quoted by Brenman-Gibson, in Brenman-Gibson 1981, p. 9.

- cf. Catalogues, New York 1996, New York 2002, New York 2006.

- cf. Harmon 1989, p. 16.

- Ibid., p. 16.

- I received instructions from Peter G. Neumann about this. I would like to express my gratitude for his support.

- cf. Herr 2003, p. 21.

- Pollack 1999, p. 265.

- cf. Letter of Jsrael Ber Neumann to Paul Klee, 01.12.1938, Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern, Schenkung Familie Klee: »Ich bin seit 1930 in immer steigendem Masse in Ihr Werk verliebt. Das ist Alles.«

- cf. Neumann 1930, p. 3.

- cf. Harter / Wiese 2011.

- Odets 1988, p. 348.

- McBride 1951, p. 35.

- Letter from Karl Nierendorf to Rolf Bürgi, February 1946, Archiv Bürgi im Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern, Schenkung Familie Bürgi: »Mr. J. B. Neumann from the New Art Circle has under consideration ›Aunt and Child‹ and ›Hard Plants‹ at a customer. These are the only two works that will be sold.«

- Letter from an unknown sender to Clifford Odets, July 31 1946. Copy SAF ZPK.

- McBride 1951, p. 37.

- Letter from an unknown sender to Clifford Odets, July 31 1946. Copy SAF ZPK.

- Letter from Clifford Odets to J. B. Neumann, June 23, 1947. Quoted by Harmon in Harmon 1989, p. 23.

- Letter from Karl Nierendorf to Clifford Odets, August 8, 1947, Lily Harmon papers, 1930-1996, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Copy SAF ZPK: »In your letter you say, that of 55 Klees, you bought only 4 or 5 from me. […] Most of your Klees have passed through my hands … you bought them indirectly from J. B. and other dealers or private collectors.«

- Letter from Clifford Odets to J. B. Neumann, June 14, 1947, quoted by Harmon in Harmon 1989, p. 23.

- McBride 1951, p. 37.

- Anonym 1947, p. 48.

- Ibid., p. 49.

- Paintings by Paul Klee. Clifford Odets Collection, Curt Valentin Papers, III B 8, Museum of Modern Art Library, New York.

- cf. Richardson 1999, p. 227.

- Waldstein 1929, p. 47.

- Cohen 2010, p. 102.

- cf. http://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2906?locale=en

- Klee 1998-2004, vol. 9, no. 6762a.

- Letter from Curt Valentin to Clifford Odets, without date (ca. Jun 1947). Curt Valentin Papers, Museum of Modern Art Library, New York.

- Letter from Curt Valentin to Clifford Odets, September 16, 1947. Curt Valentin Papers, Museum of Modern Art Library, New York.

- cf. Catalogue, San Francisco/Portland/Detroit /St. Louis/New York/Washington/Cincinnati 1949/1950, no. 39.

- Letter from an unknown sender to Clifford Odets, July 31 1946. Copy SAF ZPK.

- cf. Catalogue, Philadelphia 1944, no. 47.

- Huggler 1969, p. 93.

- cf. Catalogue, New York 1952, no. 28.

- cf. Scott 1998.

- cf. Catalogue, New York 1966, lot 59.

- Hultberg 2001, p. 26.

- cf. Catalogue, New York 1969, lot. 74, 75, 76, 77.

- Odets 1961, without pages.

- Letters from Clifford Odets to J. B. Neumann, June 14, 1947, quoted by Harmon in Harmon 1989, p. 23.

- cf. Haxthausen 2006, p. 171.

- Greenberg 1941, p. 229.

- cf. Herr 2003 p. 94.

- Klee 1948, pp. 54-55.

- Clifford 1959, without pages.

Bibliography

Monographs and essays

Anonym 1947

Anonym, »Clifford Odets«, Reviews & Previews, in: Art News, February 1947, pp. 48-49.

Brenman-Gibson 1981

Margaret Brenman-Gibson, Clifford Odets. American Playwright. The Years from 1906 to 1940, New York 1981.

Cohen 2010

Lola Cohen, The Lee Strasberg Notes, New York 2010.

Greenberg 1941

Clement Greenberg, »On Paul Klee (1879-1940)«, in: Partisan Review, vol. 8, no. 3, May-June 1941, pp. 224-229.

Harmon 1989

Lily Harmon, »The Art Dealer and the Playwright: J. B. Neumann and Clifford Odets«, in: Archives of American Art Journal, vol. 29, no. 1&2, 1989, pp.16-26.

Harter / Wiese 2011

Ursula Harter, Stephan von Wiese (ed.), Max Beckmann und J.B. Neumann. Der Künstler und sein Händler in Briefen und Dokumenten 1917-1950, Köln 2011.

Haxthausen 2006

Charles Werner Haxthausen, »A ›degenerate‹ abroad: Klee’s reception in America, 1937-1940«, in: Catalogue, Klee and America, Neue Galerie, New York, 10.03.-22.5.2006; The Phillips Collection, Washington, 16.06.-10.09.2006; The Menil Collection, Houston, 06.10.2006-14.01.2007, pp. 158-177.

Herr 2003

Christopher J. Herr, Clifford Odets and American political theater, Westport 2003.

Huggler 1969

Max Huggler, Paul Klee. Die Malerei als Blick in den Kosmos, Frauenfeld/Stuttgart 1969.

Hultberg 2001

John Hultberg, »Breaking the Picture Plane: Reflections on Painting«, in: Art Criticism, vol. 17, 2001, no. 1, pp. 6-45.

Klee 1948

Paul Klee, On Modern Art, London 1948.

Klee 1998-2004

Paul Klee. Catalogue raisonée, ed. by the Paul-Klee-Stiftung of the Kunstmuseum Bern, Bern 1908-2004, 9 vols.

McBride 1951

Henry McBride, »Rockefeller, Whitney, Senior, Odets, Colin«, in: Art news, vol. 50, no. 4, June-July-August 1951, pp. 34-37; 59-60.

Neumann 1930

Jsrael Ber Neumann, »Paul Klee«, in: Artlover, Bd. 3, no. 1, 1930, pp. 3-7.

Odets 1959

Odets Clifford, “The world of Paul Klee”, in: Artlover. J. B. Neumann’s Bilderhefte. Anthologie d’un marchand d’art, New York 1959.

Odets 1961

Clifford Odets, »Willem de Kooning, the painter«, in: Catalogue, Willem de Kooning, 1961, Paul Kantor Gallery, Beverly Hills, without pages.

Odets 1988

Clifford Odets, The Time is Ripe: The 1940 Journal of Clifford Odets, New York 1988.

Pollack 1999

Howard Pollack, Aaron Copland. The life and work of an uncommon man, New York 1999.

Richardson 1999

John Richardson, The sorcerer’s apprentice: Picasso, Provence, and Douglas Cooper, New York 1999.

Scott 1998

Yvonne Scott, »Paul Klee’s ›Anima errante‹ in the Hugh Lane Municipal Gallery, Dublin«, in: The Burlington Magazine, vol. 140, no. 1146, September 1998, pp. 615-618.

Waldstein 1929

Agnes Waldstein (ed.), Museum Folkwang, Band 1, Moderne Kunst, Essen 1929.

Catalogues of exhibitions and auctions

Philadelphia 1944

Paul Klee. Paintings, Drawings, Prints. The Philadelphia Art Alliance, 2nd Floor Galleries, 14.03.-09.04.1944.

San Francisco/Portland/Detroit /St. Louis/New York/Washington/Cincinnati 1949/1950

Paintings, drawings, and prints by Paul Klee from the Klee Foundation, Berne, Switzerland with additions from American collections, San Francisco Museum of Art, 24.03.-02.05.1949; Portland Art Museum, 16.05.-21.06.1949; The Detroit Institute of Arts, 15.09.-09.10.1949; The City Art Museum of St. Louis, 03.11.-05.12.1949; The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 20.12.1949-14.02.1950; The Phillips Gallery, Washington, D.C., 04.03.-10.04.1950; The Cincinnati Art Museum, 19.04.-24.05.1950.

New York 1952

Paul Klee, New Art Circle J. B. Neumann, New York, 13.04.-30.05.1952.

New York 1966

The Collection of Twentieth Century Paintings and Sculptures Formed by the Late G. David Thompson of Pittsburgh. PA. New York, Parke-Bernet Galleries, Inc, 23.-24.03.1966.

New York 1996

In Hell + Why: Clifford Odets, Paintings on Paper from the 1940s and 1950s, Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, New York, 11.04-08.06.1996.

New York 2002

Clifford Odets: Paradise Lost, Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, New York, 09.05-29.06.2002.

New York 2006

It’s Your Birthday, Clifford Odets! A Centennial Exhibition, Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, New York, 19.05.-04.08.2006.