YUBII NODA

ZUSAMMENFASSUNG

Im Zentrum des folgenden Beitrags stehen Paul Klees Werke Chinesisches Bild und Chinesisches II, die anfänglich als ein Bild konzipiert und unter der Nummer 235 vom Künstler in seinem eigenhändigen Oeuvrekatalog eingetragen worden waren. Zu einem späteren Zeitpunkt schnitt Klee das Gemälde in zwei Teile, die er separat rahmte. Zudem bezeichnete er die ursprünglich rechte Hälfte auf der Rückseite als »Chinesisches II« und gab dem neu entstandenen Werk die Nummer »235 bis«. Durch den Zusatz «bis» (lateinisch für: noch einmal) dokumentierte Klee, dass die beiden Bilder zusammengehören, was auch sofort evident wird, wenn die (Abbildungen der) beiden Werke nebeneinander gehalten werden. Will Grohmann hatte zwar bereits in seiner Klee-Monografie von 1954 auf diese Tatsache hingewiesen, doch geriet diese Information in Vergessenheit, da Klee in seinem Oeuvre-Katalog keine Anpassung des ursprünglichen Eintrags vornahm, und die beiden Werke an unterschiedliche Käufer gingen. Chinesisches II konnte erst 2009 im Zentrum Paul Klee untersucht werden. Dies erklärt, warum Chinesisches Bild und Chinesisches II nicht in der Monografie zum Thema der zerschnittenen Werke Paul Klees von Wolfgang Kersten und Osamu Okuda von 1995 publiziert wurden.

Die Analysen von Noda erfolgen vor dem Hintergrund von Klees Interesse am Fernen Osten, die der Maler mit zahlreichen Zeitgenossen und später auch mit seinen Künstler-Kollegen am Bauhaus teilte. Hervorgehoben wird die Rolle von Johannes Itten, der von 1919 bis 1923 am Bauhaus einen Vorkurs ausrichtete. Die Autorin sieht in diesem Interesse an Ostasien, das auch eine Beschäftigung mit Taoismus und Buddhismus einschloss, den Wunsch, sich in einer schwierigen Zeit neue Wertvorstellungen zu geben. Zudem ruft die Autorin in Erinnerung, dass Klee am Bauhaus den in keiner Weise abwertend gemeinten Übernahmen «Buddha» erhalten hatte.

Der zweite, sehr viel detaillierter ausgearbeitete Hintergrund, vor dem Noda ihre Forschungen entwickelt, sind die Bücher aus dem Besitz von Paul Klee, die als Ensemble erhalten geblieben sind und sich heute in der Sammlung des Zentrums Paul Klee befinden. In ihrer Analyse unterscheidet Noda zwei Phasen: In der ersten, von 1909 bis zum Ende des Ersten Weltkriegs dauernden Zeitspanne, gelangten vor allem Publikationen über fernöstliche Poesie und Literatur in Klees Privatbibliothek, von 1919 bis 1924 machten Bücher über die bildende Kunst des fernen Ostens den Hauptteil der Neuzugänge aus. Noda weist darauf hin, dass sich Klees Werke aus diesem Zeitraum häufig auf östliche Themen beziehen. Ihre Beobachtungen, die sie mit Querverweisen zur politischen Geschichte des Deutschen Kaiserreichs verknüpft, untermauert Noda mit Äusserungen Klees aus seinen Tagebüchern und Briefen.

In der anschliessenden Analyse der beiden Werke, die sie Klees Schriftbildern zuordnet, interpretiert Noda die männliche Figur von Chinesisches II als Selbstporträt, mit dem sich der Künstler – nach dem Vorbild von van Goghs Selbstbildnis der Bayerischen Staatsgemäldesammlung – als buddhistischen Mönch zeigt. Nach Noda nahm Klee die Aufteilung in zwei Werke vor, um seinem Selbstporträt mehr Gewicht zu verleihen. Zugleich erkennt sie im Auseinanderschneiden des Werks eine Stellungnahme Klees zum Kurswechsel des Bauhauses, wo anfänglich ein starkes Interesse an östlichem Gedankengut bestanden hatte, von dem sich jedoch Gropius im Interesse einer stärkeren Zusammenarbeit mit der Industrie schon bald distanzierte. Stellvertretend dafür steht die Entlassung von Johannes Itten im April 1923, der auf diese Weise zum Symbol für die Preisgabe der ursprünglichen Ideale des Bauhauses wird.

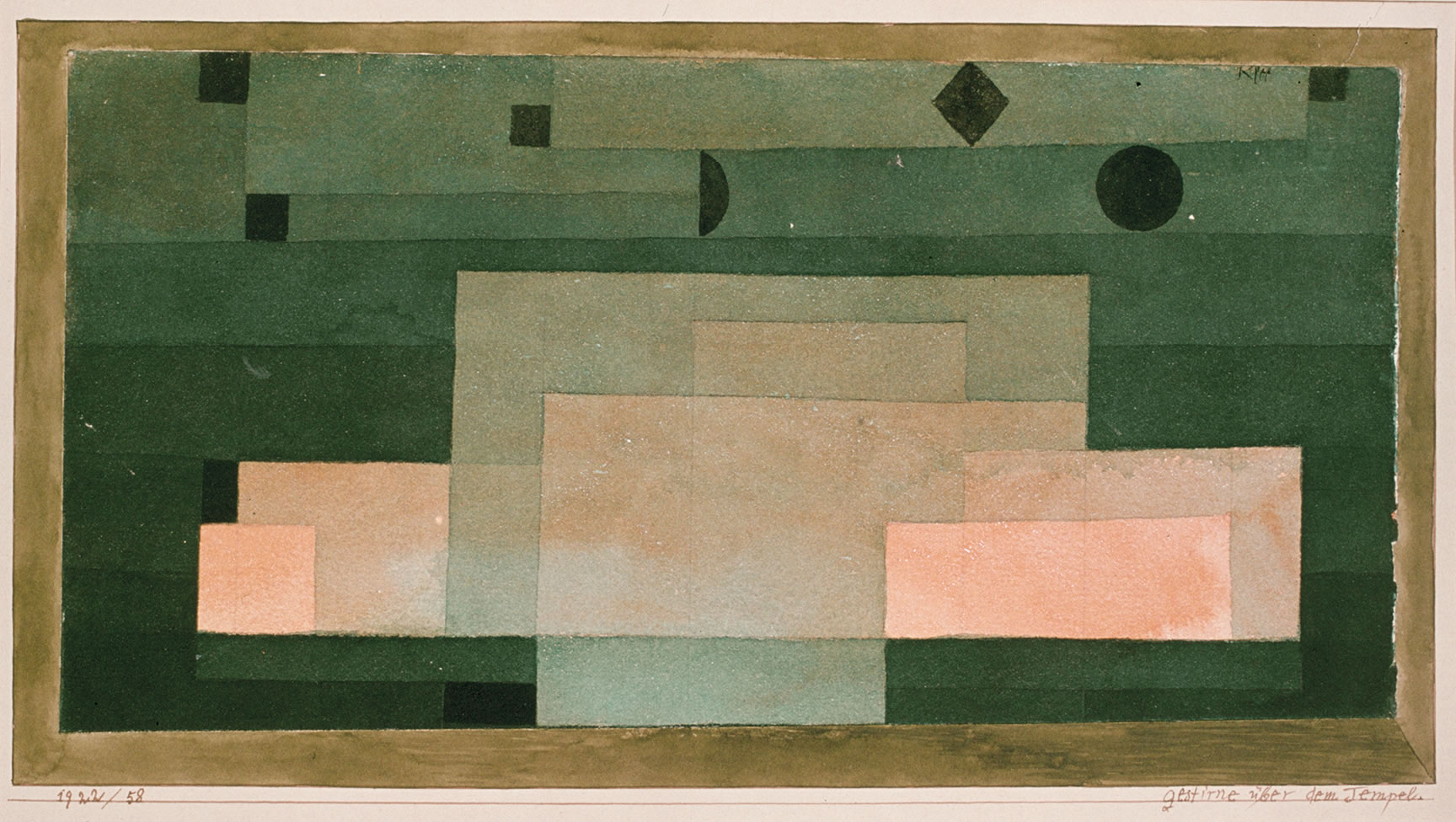

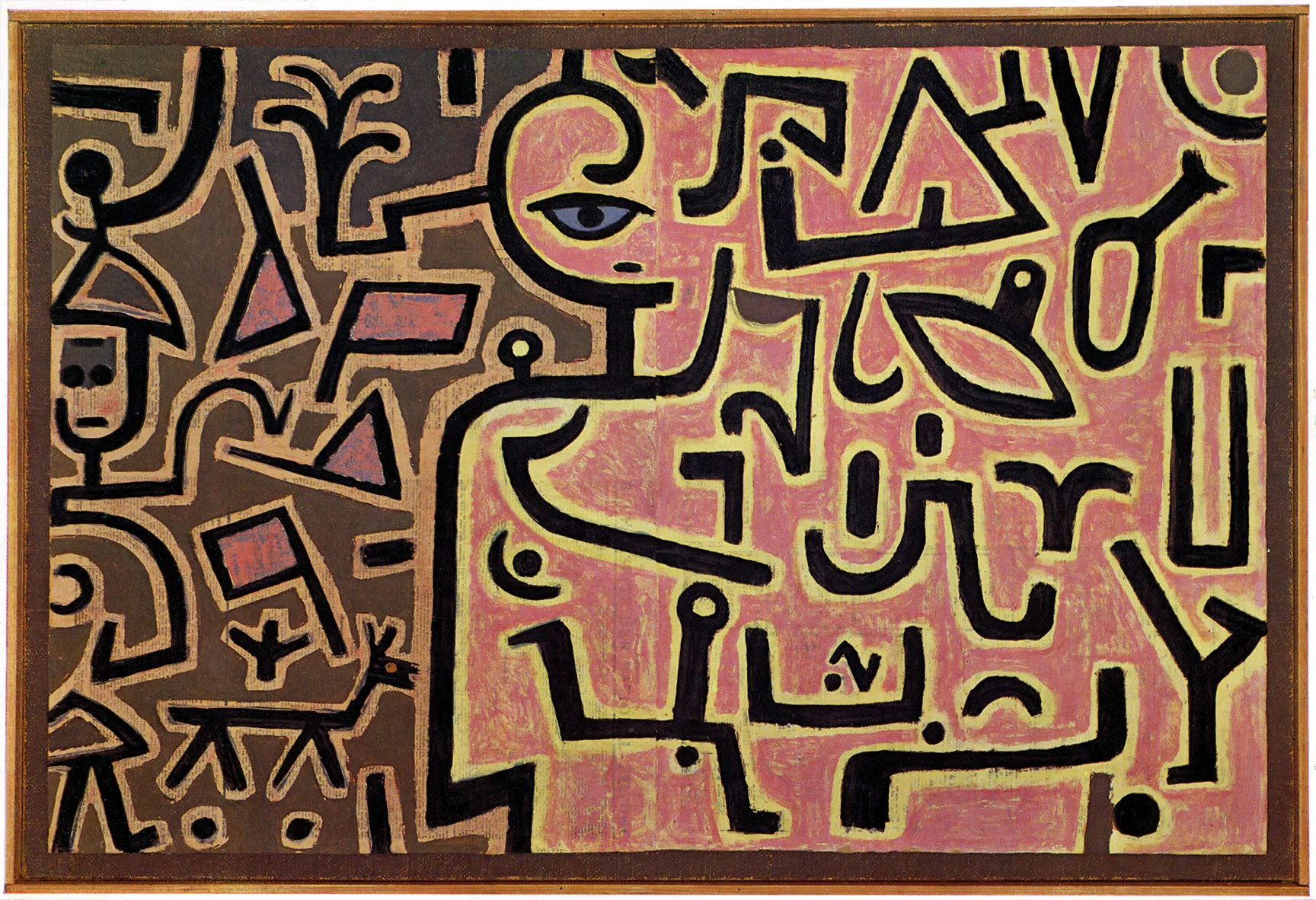

In an attempt to shed light on the Oriental interests of Paul Klee (1879 - 1940), I have examined the periods in which the artist collected books on Asia and the Orient, finding a first period from 1909 to the middle of World War I, and a second from 1919 to 1924.1 The years from 1919 to 1924 also represented a peak for Klee’s production of paintings related to Asia and the Orient. This period overlaps with the years that Klee taught as an teacher at the Bauhaus in Weimar (1921 - 25). It is likely that the keen interest of the Bauhaus community in Asia and the Orient exerted an influence on Klee. In this article I will focus on two paintings by Klee – Chinese Picture (Chinesisches Bild, 1923, 235), in the collection of the Miyagi Museum of Art [Fig. 1] and Chinese II (Chinesisches II, 1923, 235 bis), [Fig. 2] – examining Klee’s engagement with Asia and the Orient by pursuing the hitherto unresearched background to the production of these works.

1. Interest in Asia and the Orient at the Weimar Bauhaus

In the early years of the Weimar Bauhaus, there was a strong interest in esoteric spirituality and non-Western culture among the artists of this institution. The most influential figure in this regard was Johannes Itten, who was invited to teach at the Bauhaus in 1919, and who was responsible for the institution’s «Vorkurs» (preliminary course) until his resignation in March 1923. Itten, who had developed an interest in East Asian art and philosophy from around 1917, introduced the works of the Chinese and Japanese ink painters into a curriculum centered on the analysis of the works of the great masters of the past and present.2 Itten incorporated the teachings of the Persian religion Mazdaznan, which he and his colleague Georg Muche had discovered prior to being invited to teach at the Bauhaus, into his life and his classes, and generally behaved like the leader of an esoteric cult or secret society.3 This attitude led to differences of opinion with Walter Gropius, founder and director of the Bauhaus, who gave notice of the termination of Itten’s employment there in 1922. The conflict between the two, which began toward the end of 1921 also expressed in disagreement over whether the institution should emphasize individual education or increase its collaboration with industry; in the end, the Bauhaus took the latter course.4

Yet in his 1919 Bauhaus Manifesto, Gropius himself had espoused the ideal, not of mechanical production, but of »a new guild of craftsmen«, and in the early years of the Bauhaus he was, if anything, favorably disposed to esoteric spiritual tendencies5– which were shared by a number of the Bauhaus artists, including Muche, Gyula Papp, Karl Peter Röhl, Lothar Schreyer, Gunta Stölzl, Wassily Kandinsky, and Paul Klee.6 Klee was one of the people who found employment as a master at the Bauhaus through Johannes Itten. Although he distanced himself somewhat from Itten’s approach, Klee shared the rising interest in Asia and the Orient that was part of the tenor of the times just before the outbreak of World War I. This interest can be seen, not only in Klee’s work, but in the books he collected during this period. My survey of Klee’s reading, based on the books from the Klee family library in the collections of the Zentrum Paul Klee in Bern, as well as the artist’s diaries and letters to his family have revealed the following. The first peak of this collecting of books on Asia and the Orient was in the years from 1909 to the end of World War I, with the majority of the titles being works of poetry and narrative prose; the second peak came from 1919 - 24, when art books made up a high percentage of those collected.7 Klee’s collecting as a whole encompassed a variety of ages and regions, but during both the first and second peaks, titles related to China and India tended to predominate. The tendencies of the collection can probably be said to reflect rather strongly the situation and trends in German society and art from the war years into the postwar era. In particular, Klee’s collection of books on Chinese literature and Daoism is clearly connected to the popularity enjoyed by translations of Chinese poetry in the wake of the establishment of German Empire’s leasehold at Jiaozhou Bay (Qingdao) in 1898, as well as the appeal that Daoism and Buddhism had to German intellectuals searching for a new system of values from the middle of World War I to the period after Germany’s defeat. As a result of the defeat, Germany lost all of its overseas possessions, including those in China, and by the terms of the Versailles Peace Treaty the German concession in the Shandong Peninsula was ceded to Japan.8 In return, the Japanese plenipotentiary published an official statement, on the basis of an agreement with US President Woodrow Wilson, that it was Japan’s policy to restore sovereignty over the peninsula to China. In addition, in 1921 China signed with Germany its first modern treaty on equal terms with a Western power, and the result was a very positive development of Sino-German relations.9 For Klee, who had been critical of Western colonialism even before World War I,10 this must have been significant news. And Klee’s collection of books related to India must be considered in the context of Rabindranath Tagore’s influence in Germany and the sympathy which the defeated German nation felt for the rise of the Indian independence movement after 1919.11

Even before the war had ended, in works deriving from his 1914 trip to Tunisia and in the series of »word pictures« (Schriftbilder) he made from 1916 - 21, Klee was incorporating Oriental themes into his work, but as one might suspect, it was during the second peak of his collecting that he produced a large number of works related to Asia and the Orient. These tend to be divisible into the categories of figure painting and landscape, with a variety of Asian place names represented in their titles. The richness of these works was no doubt strongly influenced by the growing interest in the cultures of Asia and the Orient within the Weimar Bauhaus at the time – a trend which was not limited merely to the imagination of these artists, but also developed into more active and tangible forms of cultural exchange. One example of this was the Bauhaus exhibition in Calcutta, in planning from October 1922 until March of the following year, and eventually opening on 23 December 1923. The exhibition was spearheaded by Abanindranath Tagore, nephew of Rabindranath and secretary of the Indian Society of Oriental Art. Georg Muche was responsible for selecting the works to be exhibited. The occasion which inspired this exhibition was probably a poetry reading on 7 May 1921 at the German National Theater in Weimar celebrating Rabindranath Tagore’s sixtieth birthday.12 In connection with this event, Itten drew a pencil portrait of Tagore in May 1921 (preserved in the Itten Archive, Zurich).13 Partha Mitter suggests that it is likely that Tagore, who visited the Bauhaus on this occasion and was quite impressed by it, may have proposed the idea of an exhibition under the auspices of his nephew.14 Nine new works by Klee from 1922 were exhibited in Calcutta. The Central State Archive of Thüringen in Weimar has a catalogue of the works submitted to the exhibition, of which List No. 4 comprises works by Klee, whose titles are as follows:15 Red-Violet / Yellow-Green Gradation (1922, 64), Two Kiosks (1922, 66), Queen of Hearts (1922, 63), Mask (1922, 61), Locks (1922, 60), Stars over the Temple (1922, 58) [Fig. 3], Face of a Flower (1922, 57), Evening Sun (1922, 62), and Palace (1922, 65). All of these works were characterized by a rhythmical geometric organization of the picture plane employing gradations of transparent watercolor, but also incorporated various fairy-tale or fantastic elements. The same year, Klee also painted Indian Flower Garden 1922, 28 [Fig. 4].

This is an abstract landscape, with stylized flowers lyrically arrayed as if on a musical staff in a work that belongs to the lineage of Schriftbilder mentioned earlier. Klee is believed to have had in mind the world of Tagore’s Gitanjali and The Gardener when creating this painting. In a letter of October 1917 to his wife Lily, Klee mentions a collection of Tagore’s poetry,16 and the participation of his father Hans Klee in the reading of a free verse translation of The Garden at the Town Hall (Rathaus) in Bern on 1 November 1920 is believed to have focused his attention on this work.17 Indian Flower Garden employs watercolor and colored chalk over a prepared ground of English red mixed with wheatpaste applied to paper; this was then mounted on cardboard, with the exposed borders surrounding the work painted with ink and watercolor. While depicting a fantastic Indian flower garden, at the same time the dark English red ground establishing the fundamental tonality of the painting may also hint at the legacy of British rule in India and the impact of the Indian independence movement of which Tagore was also a participant.

Something which tends to substantiate Klee’s interest in India’s political situation is the fact that Klee received copies of Sattar M. A. Kheiri’s Indian Miniatures of the Islamic Era (Berlin, 1921) from both his son Felix Klee in 1921 and a favorite student in Bern, Marguerite Frey-Surbek, in 1923.18 This book was also in the library of the Weimar Bauhaus.19 In his preface to the book, Kheiri criticized British rule and Western colonialism from the perspective of an Indian, and expressed the intention of introducing the miniatures of the Islamic era (16th - 19th centuries) as an aspect of Indian art hitherto unappreciated in the West.20 From such reading as this, and the general environment of the Weimar Bauhaus, we can see how Klee might have developed a positive engagement with the art and society of Asia and the Orient, and how this interest could have developed into a wellspring of his artistic production – sometimes influencing even his choice of materials and his process of artistic production.

Next, I would like to look at the background to that artistic process as embodied in two works that clearly represent Klee’s interest in Asia and the Orient at this time – Chinese Picture and Chinese II, painted in 1923.

2. Chinese Picture and Chinese II: Separated at Birth

Although Will Grohmann observed as early as 1954 that Chinese Picture and Chinese II were originally part of a single composition, no subsequent work was done to confirm this suggestion.21 In this paper I would like to explore this possibility. Since the whereabouts of Chinese II are unknown, photographic evidence will provide the basis for this investigation.

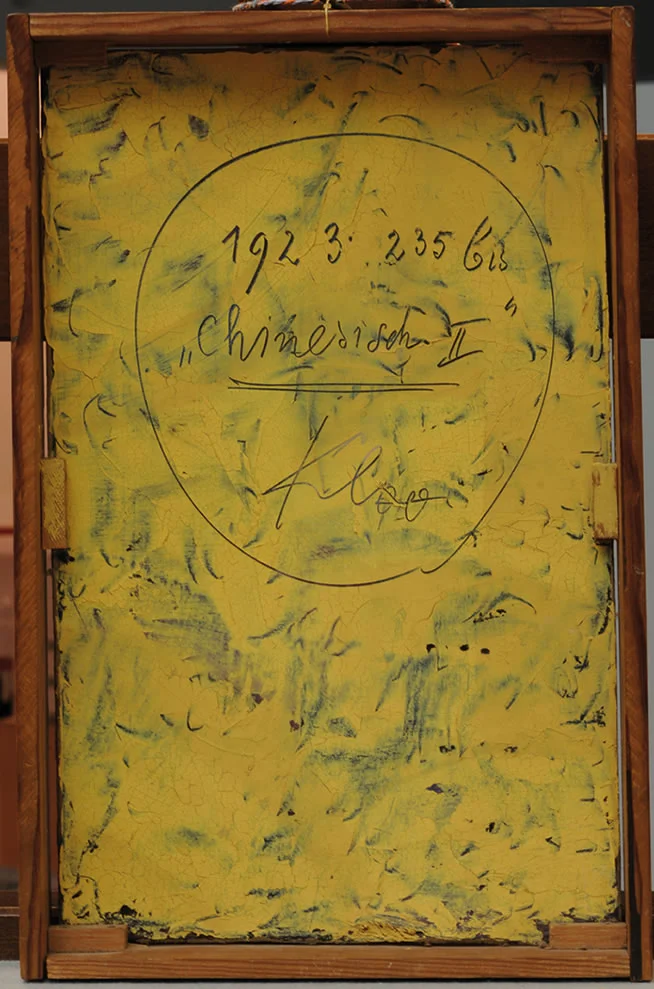

The titling of the two works in itself suggests an association, that is borne out by the following two points. First, in Klee’s handwritten personal catalogue of his work, Chinese Picture is recorded as opus number 235 of the year 1923, while there is no entry for Chinese II. However, on the verso of Chinese Picture II is an inscription in Klee’s hand which reads »1923 235 bis "Chinesisches II" Klee« (»235 bis« signifying no. 235, part 2) [Fig. 5]. From this numbering, the relationship between the two paintings is apparent. Moreover, from the following we can determine that the wood frame surrounding Chinese II was attached by Klee himself. In the photograph of the verso of the painting, we can see that it is covered with a roughly applied coat of yellow paint, overwritten with the title, number, and Klee’s signature and thus naturally indicating that it was Klee himself who applied the paint. And since the pieces of wood holding the painting within the frame are also covered with this paint, it is reasonable to assume it was Klee himself who placed the picture in the frame.

Second, in a letter dated 5 September 1945 from Walter Lotmar – son of Fritz Lotmar, a Bern neurologist who was an old friend of Klee – to Klee’s wife Lily, Lotmar related that he has a friend named Picken engaged in cultural affairs work in China who would like to purchase both works, and asks if Lily still has them in her possession. In other words, this hints that at this point as well, the two works were being considered as a pair, or at least as very closely related. But in the event, neither work joined Picken’s collection, and each was fated to end up in different hands. According to Klee’s catalogue raisonné,22 and the information on provenance in the records of Zentrum Paul Klee, Chinese Painting was in the possession of Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler’s Gallery Simon in Paris until 1938, at which time it passed through the Karl Nierendorf Gallery into the possession of American modern art collectors Stanley Rogers Resor and his wife Helen. It was inherited by Ann Resor and her husband, the American poet James Laughlin, becoming part of the Ann Resor Laughlin estate after her death, and was eventually put up for auction at Sotheby’s in New York in May 1991. From there it passed the same year from the Natalie Seroussi Gallery in Paris to the Satani Gallery in Tokyo, and finally entered the collection of the Miyagi Museum of Art. On the other hand, according to the records of provenance at Zentrum Paul Klee, Chinese II was owned by the Swiss publisher Hans Meyer-Benteli and his wife Erika, becoming part of the collection of their estate. It was appraised by the Zentrum Paul Klee in 2009 and certified as a genuine work by Klee, but its present ownership is unknown. The photos used as illustrations for this article were all taken at the time of the appraisal at the Zentrum Paul Klee.23

Dimensions of the two paintings are as follows: both are 31 cm in height; Chinese Picture is 17 cm in width, while Chinese II is 19.3 cm. Chinese Picture was mounted by Klee himself on cardboard, which was in turn painted with oil paint, and then framed. Visual comparison of the two paintings reveals two incomplete forms in the upper right hand corner of Chinese Picture and two incomplete forms in the upper left corner of Chinese II. If the images of the two paintings are aligned along their vertical dimension, these forms match up perfectly; the first becoming a leaf or slender cloudlike shape, the second suggesting a lamp formed by a triangle and an oval [Fig. 6]. Moreover, if we look closely, there is hatching in the base of the triangular portion of this lamplike form in Chinese II that is matched by hatching running in exactly the same direction in Chinese Picture. As a result, I believe that Chinese Picture once occupied the left half and Chinese II the right half of a single painting that at some point in the process of creation Klee divided and separated along the vertical axis – though I must state that this hypothesis is based solely on the photographic evidence taken at the time of the appraisal of Chinese II. The selection of where to make the cut separating the two halves appears to have been carefully calculated, at least from a formal perspective, to cause the least damage to the forms represented in the painting – the division of the two small forms in the upper part of the painting, mentioned earlier, being the only sacrifice of this kind.

Next I would like, insofar as possible, to take a fresh look at the process of production of this painting. In Klee’s manuscript catalogue of his own work, production details for Chinese Picture are recorded as: »Öl = und Wasserfarben (kl. Gemälde in der Art der chin. Lackmalerei) Pappe« [Oil and watercolor (a small work in the manner of Chinese lacquer painting) Cardboard]. This is speculative, but I believe the process went something like this. Klee first applied a ground to a piece of cardboard, drew the outlines of the forms on it, and applied green, brown, and red watercolor to them. Then, preserving the outlines of the forms, he applied a transparent glaze of thinned black oil paint to the entire ground surrounding them. Over this he applied another glaze of transparent paint. Chinese II no doubt followed a similar process. If we look closely at Chinese Picture, there is a horizontal band in about the middle third of the painting to which another layer of black paint was applied – producing a richer, glossier black than the areas above and below that had earlier received the glaze of black oil [Fig. 7].

This is what Klee described as a technique »in the manner of Chinese lacquer painting«. However, amid the books Klee collected on Asia and the Orient, we do not find any with illustrations of Chinese lacquer painting. A Japanese artist named Shibata Zeshin, active in the late 19th century, is renowned for having invented and developed his own unique technique, based on traditional methods, for paintings employing lacquer on paper or fabric – but Klee was much more likely to have been acquainted with, and had in mind, the type of decorative patterns found on lacquerware craft objects.24 Among the techniques of Chinese lacquerware is one called diao qi, or carved lacquer, that seems close to Klee’s artistic process. Diao qi involves the application of numerous layers of lacquer, which are then carved or incised to create a pattern. Particularly when this carving reveals an underlying layer of color as part of the pattern, it might be said to come close to what Klee was doing. Where could Klee have learned of such a technique? In a letter of 5 March 1903 to his fiancée Lily Stumpf, Klee mentions that he has been reading The Art of Pre-Christian and Non-Christian Peoples, the first volume of Karl Woermann’s series The History of Art of All Ages and Peoples [Karl Woermann, Geschichte der Kunst aller Zeiten und Völker, Bd. 1: Die Kunst der vor- und außerchristlichen Völker, Leipzig/Wien 1900].25 This book touches upon the craft of Chinese lacquerware, explaining that »various layers are applied one atop the next, from which a relief carving is made« (p. 517) – a description that would seem to refer to the diao qi technique. In his artistic production, it seems likely that Klee remembered this technique he had learned of in his younger days. Yet the actual appearance of Chinese Picture and Chinese II seems to more closely resemble that of the Japanese lacquer technique known as maki-e.

From 1919 into the early 1920s, produced a series of works on Chinese themes: the figure paintings With the Chinese 1920, 19, Chinese Novella 1922, 80, The Monkey Sun 1922, 217, and Chinese Porcelain 1923, 234; the landscape The Way from Unklaich to China 1920, 153; and Exotic River Landscape 1922, 158, which combines aspects of both Chinese landscape and bird and flower genres. But Chinese Picture and Chinese II were unusual in that they were related to China not only in terms of content, but in that China also inspired the technique of their production, producing a unique result.

3. Chinese Picture – Self-Portrait as a Buddhist Monk

If Klee did indeed cut this painting in half, the question remains why. If we consider what was presumably the prior state of the composition, the male figure at the lower right of Chinese Picture stands out from amid the other symbolic forms, and it seems likely that Klee experimented with cutting the original painting in two for the purpose of giving greater emphasis to this figure.

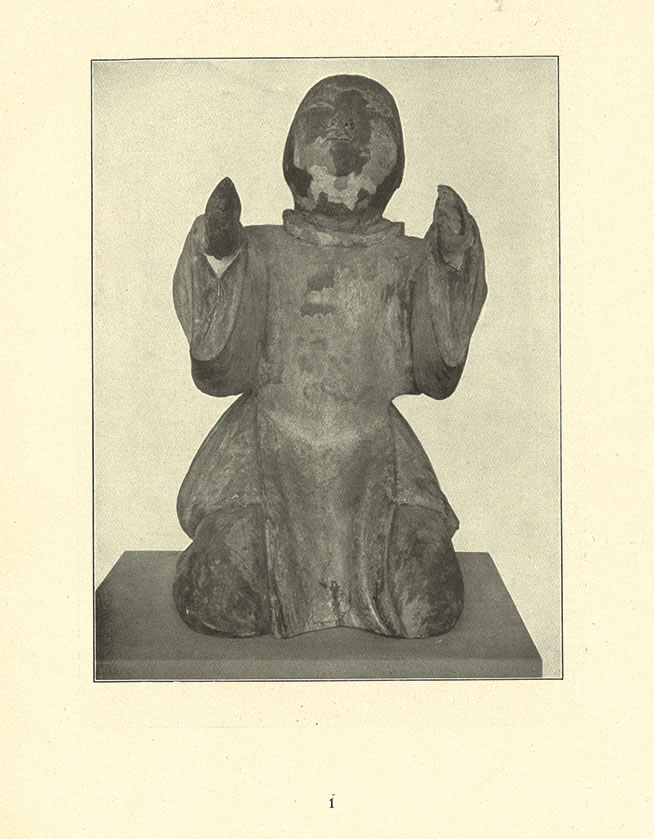

On the other hand, a number of the forms depicted in Chinese II seem to draw inspiration from Klee’s collection and reading of books on Asia and the Orient. The key element among them is the figure just right of the center of the picture, which appears to be wearing a kimono-like garment with broad sleeves and standing with upraised arms. This faceless figure with its simple form gives the impression of being a sculpture or doll rather than a human being. It is possible that in making this figure, Klee referenced a photograph in Karl With’s The Monumental Sculpture of Asia (a copy of which was given to Klee as a Christmas present by his son Felix in 1921) of a sculpture captioned »Japan. Image of Prince Shōtoku as a child.«26 [Fig. 8].

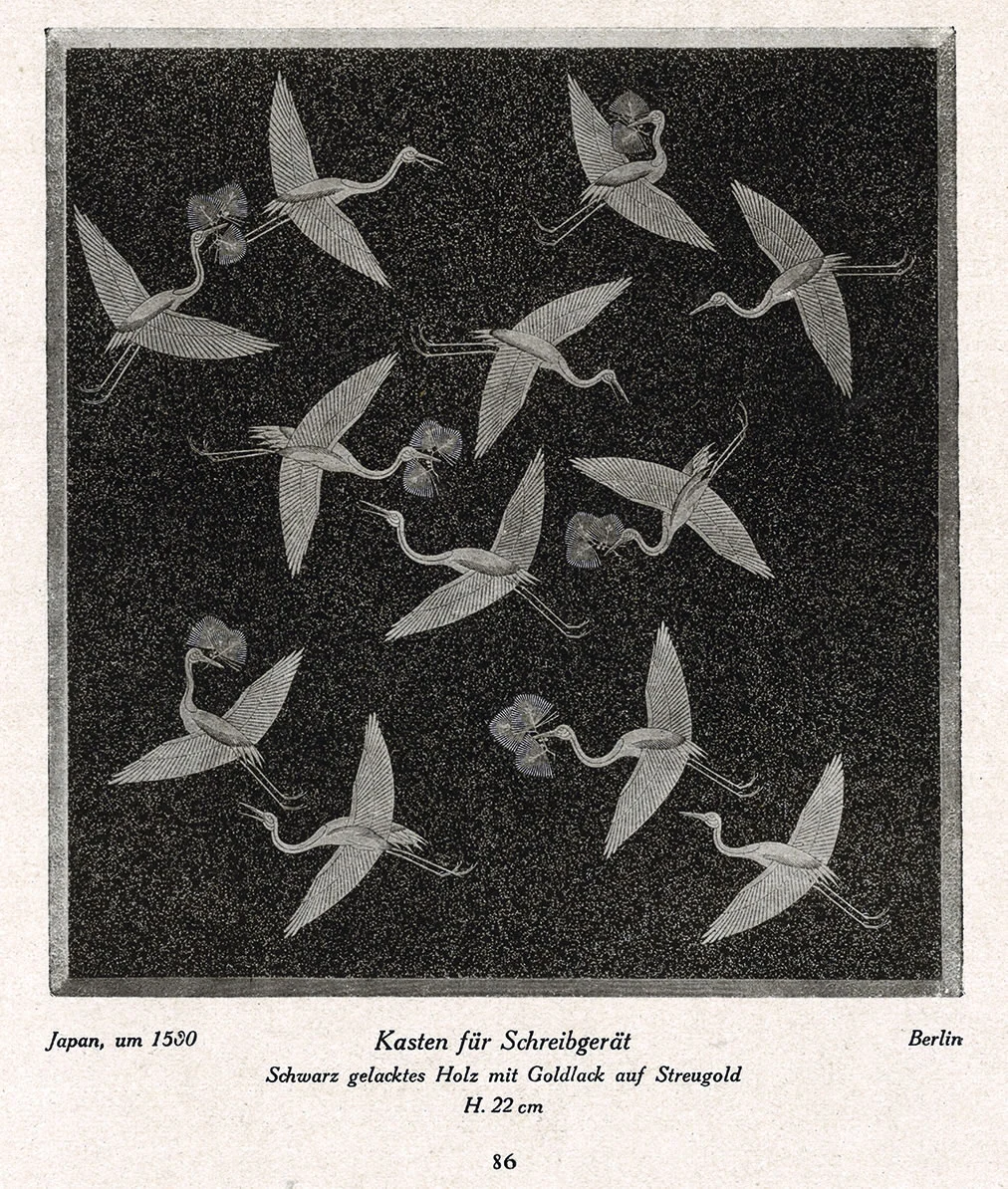

The only illustration amid Klee’s collection of books on Asia and the Orient that so closely resembles the specific costume and pose of the figure in Chinese II is not a Chinese image at all, but this photo of a sculpture of Japan’s Prince Shōtoku. It is the first plate in With’s book, and he alludes to it dramatically in his preface, where it s described in the following manner: »… a child, already showing the splendid promise of youth, kneels with arms outstretched towards heaven in prayer and supplication…«27 In Klee’s painting, above this figure a balloon floats upward, while to the upper right of the balloon, as if in response to the gesture of the figure, an arrow descends from the heavens towards the figure’s hand. Klee seems to be taking a hint from With’s description, giving symbolic representation to the human longing to ascend into the heights of heaven. In addition, a bird resembling a stylized crane is depicted in the lower part of the composition. This may have been inspired by an illustration and the corresponding description in Otto Kümmel’s The Art of East Asia (Berlin, 1921) of an inkstone box, made in Japan in about 1500, featuring a design of cranes with pine branches in their beaks.28 [Fig. 9] In this case, the illustration is a black and white photograph of a piece of lacquerwork, with the lacquer ground appearing as a black similar to that used in Chinese Picture. The book itself was used by Itten at the Bauhaus as a reference text for exploring ink painting in his classes, and there is ample reason to believe that he could have shown it to Klee.29 Of this work of maki-e style lacquer, Kümmel writes: »The cranes with the pine branches in their beaks symbolize the Isle of the Immortals, which according to Chinese legend is located in distant eastern seas, inapproachable by human beings. The reason for this was that for the Chinese, and perforce for the Japanese as well, the crane and the pine embodied a youthful vigor and beauty even into the extremity of old age.«30 The crane with the pine branch in its mouth was imported to Japan from China as a stock motif of bird-and-flower painting, where it was also associated with Hōraisan, the distant isle of immortality. In Klee’s painting, the bird does not hold a pine bough in its beak, but its beak points in the direction of a flower that would seem to suggest the pine boughs carried by the cranes on the inkstone box illustrated in Kümmel’s book. These motifs are connected with those mentioned earlier – the figure, the balloon, the arrow – as representing the human longing for ascension, and may be regarded as supporting the sprightly world of the imagination that the Orient opened to Klee. Moreover, it seems likely that this book might have provided other images besides this inkstone box – photographs of other maki-e pieces and lacquerware from the Shōsoin repository – as reference for Klee in creating works of artmaking pieces »in the manner of Chinese lacquer painting.« Otto Kümmel was a historian of East Asian art and first director of the East Asian department of the Berlin Ethnological Museum. He was involved in mounting an exhibition in Munich entitled Japan and East Asia in Art31 in 1909, when Klee was living there. In addition, Kümmel gave a lecture on »Ancient Chinese Painting« on 28 October 1921 at the Jena Art Association, where Klee would have four exhibitions of his work and deliver the lecture »On Modern Art« in 1924.32 Jena is located close to Weimar, and Klee’s friend, the Constructivist designer and writer Walter Dexel served as the exhibitions director for the Jena Art Association.33 As the Art Association was frequented by members of the Bauhaus, it is quite possible that Klee could have attended Kümmel’s lecture, as well as a lecture on »The Art of Ancient India« given there on 15 November 1921 by Karl With, author of The Monumental Sculpture of Asia.34 Klee owned a total of three volumes on Asian art written by With and published in 1921 and 1922.35 All of this supports the idea that at the time he produced Chinese Picture and Chinese II, Klee was at least aware of the writings of Kümmel and With. And when Klee Asian or Oriental art as a springboard for his own work, his imagination tended to travel quite freely in space and time – for example, in the resemblance between the compositions of Two Vignettes for the Psalms (1915, 81) and »High and Shining Stands the Moon«: Composition on a Chinese Poem by Wang Seng-yu, Part 1 (1916, 20). This suggests that when Klee drew inspiration for the motifs in Chinese Picture and Chinese II from Japanese as well as Chinese art, this was not because he was unable to distinguish between the two, but that he intentionally chose not to, keeping Kümmel’s explanation of the relationship between Chinese and Japanese culture in mind and allowing his imagination to roam freely between the two as he developed his own work.

If some of the forms in Chinese II took hints from Klee’s cllection of books, then certain characteristics of the head of the male figure in Chinese Picture recall Buddhist images, and suggest the possibility that it may be a self-portrait as a Buddhist monk. Klee could have gained information about Buddhist monks from such sources as the depiction of Xuanzang Sanzang in Richard Wilhelm’s translation Chinese Folktales (Jena, 1914).36 Klee’s interest in this theme found early expression in a hand-puppet he made for his son in 1920, Untitled (Buddhist Monk) [Fig. 10]. He was also known – respectfully – by students and colleagues at the Bauhaus as »The Buddha«.37 As mentioned earlier, in the period after the defeat in World War I, not only members of the Bauhaus but German intellectuals in general were looking to Buddhism and Daoism as potential guides to a new path leading away from the discredited traditional values of the West.38

In this regard, it is likely that Klee was aware of Vincent Van Gogh’s Self-Portrait as a Buddhist Monk (1888) [Fig. 11]. This painting was made during Van Gogh’s time in Arles, and was originally owned by Paul Gauguin, who traded it for a self-portrait of his own, Le Misérables (1888). Around 1905, about fifteen years after Van Gogh’s death in 1890, his works finally began to sell and achieve some degree of economic success.39 According to Gesa Jeuthe, in 1906, the director of the National Gallery in Berlin, Hugo von Tschudi, bought Van Gogh’s Self-Portrait from Paul Cassirer, owner of a Berlin gallery, secretary of the Berlin Secessionists,

and editor of the journal Kunst und Künstler (Art and Artists).40 Tschudi was a champion of modern art who was responsible for introducing to the National Gallery the art of the period from the French Barbizon school of the 19th century onward.41 Hounded from his post by conservative forces, Tschudi left Berlin in 1909 for Munich, where he was appointed director of the Bavarian State Painting Collections. The Van Gogh Self-Portrait went with him. Tschudi gave enthusiastic support to the young artists of the Blaue Reiter movement, but passed away in 1911. After World War I, in 1919, the Van Gogh was purchased from Tschudi’s widow by the Munich State Gallery.42 Until 1938, when it was confiscated by the Nazis, the Van Gogh Self-Portrait was on permanent display as a memorial to Tschudi and to the contribution he made to the museum and to modern art. Klee, who was a participant in the Blaue Reiter movement, almost certainly had the opportunity to see this much-discussed painting during his time in Munich.

Even before World War I – that is, from the time Van Gogh first began to be introduced and talked about in Germany – Klee showed an interest in Van Gogh’s paintings and letters. For Christmas in 1907, his wife Lily presented him with a copy of a German translation of a selection of Van Gogh’s letters published in 1906 by Bruno Cassirer.43 In two autobiographical fragments written at the request of Wilhelm Hausenstein, Klee notes that he read the Van Gogh letters in 1908, and that same year saw two Van Gogh exhibits, at the Brakl and Zimmerman galleries.44 Additional bibliographic materials related to Van Gogh in Klee’s collection published prior to World War I included a collection of Van Gogh paintings published in 1912, and Vincent Van Gogh by Julius Meier-Graefe, published in 1910 and given to Klee for Christmas that year by his wife Lily.45 Since Klee had been interested in Van Gogh from his younger days, it seems no coincidence that Lily would present Klee with a German translation of Van Gogh’s letters to his brother Theo46 in 1919 – the year that the Van Gogh self-portrait owned by Tschudi became part of the Bavarian State Painting Collections. The title of Van Gogh’s Self-Portrait as a Buddhist Monk was rendered in German simply as Selbstbildnis (Self-Portrait).47 But in this collection of

Van Gogh’s letters, Van Gogh writes as follows of the self-portrait he would trade to Gauguin:

»My portrait, which I am sending to Gauguin in exchange, holds its own, I am sure of that. I have written to Gauguin in reply to his letter that if I might be allowed to stress my own personality in a portrait, I had done so in trying to convey in my portrait not only myself but an impressionist in general, had conceived it as the portrait of a bonze, a simple worshiper of the eternal Buddha.

And when I put Gauguin’s conception and my own side by side, mine is as grave, but less despairing….

Someday you will also see my self-portrait, which I am sending to Gauguin, because he will keep it, I hope.

It is all ashen gray against pale veronese (no yellow). The clothes are this brown coat with a blue border, but I have exaggerated the brown into purple, and the width of the blue borders.

The head is modeled in light colours painted in a thick impasto against the light background with hardly any shadows. Only I have made the eyes slightly slanting like the Japanese.« [Letter No. 529 in the German translation Klee acquired in 1919]48

Reading this letter, it is apparent that it describes the self-portrait as a Buddhist monk that Van Gogh traded to Gauguin; this is supported by the partially effaced dedicatory inscription and signature still partially visible at the top of the painting. In addition, this painting is reproduced in Julius Meier-Graefe’s Vincent (published in 1922), which Klee owned.49

A comparison of Van Gogh’s Self-Portrait as a Buddhist Monk with the male figure in Klee’s Chinese Picture shows a number of similarities. They face in opposite directions, but both are bust-length portraits of bearded men with close-cropped hair and eyes slanting slightly upward. A photo portrait of Klee taken in 1922 [Fig. 12] shows a similar appearance of cropped hair and beard to the figure in Chinese Picture. The hand-puppet of a Buddhist monk with shaved head and slanting eyes that Klee made in 1920, mentioned above, has been described by Osamu Okuda as probably a self-portrait.50 And in Kümmel’s The Art of East Asia there is a reproduction of a painting of a Buddhist arhat (the caption says »China?«) with fierce expression and a beard [Fig. 13]. It seems plausible that Klee, taking Van Gogh’s self-portrait as a model, and enriching this image with reference to the arhat painting and other sources, produced his own self-portrait as a Buddhist monk.

Van Gogh projected his ideals of religion and community onto Japan, and painted a portrait of himself as a Buddhist monk living in that utopia.51 The Bauhaus also started out as a utopian community with strong spiritual leanings. But the Bauhaus would soon begin to distance itself from this tendency, as symbolized by the departure in April 1923 of Itten, who had stood at the apex of it. If we examine the forms surrounding the male figure in Chinese Picture, the five-pointed star on the flag at the upper left recalls the three five-pointed stars floating above the three towers of Lyonel Feininger’s illustration Cathedral, which was featured on the cover of Gropius’s Bauhaus Manifesto of 1919 [Fig. 14]. Stars also feature prominently as a motif in the design submitted by Elfriede Knott in the student competition to design an official school emblem for the Bauhaus [Fig. 15].

And in 1923, when Klee painted Chinese Picture, he produced other works with starry themes, such as Assyrian Game (1923, 79) in which five-pointed stars romp and rotate amid a variety of others; and Connected to the Stars (1923, 159) [Fig. 16], which according to Klee’s son Felix was based on impressions of a festival at the Bauhaus.52 From this it is possible to speculate that the flag with its five-pointed star appearing in Chinese Picture symbolizes the Bauhaus. Then, in the lower left corner of the painting, we find a geometric form closely resembling one which Klee drew to represent the principle of compositional symmetry in the notes on pictorial morphology he made for a class at the Bauhaus on 12 December 1921.53 [Fig. 17]. Above the head of the figure floats a geometric form based on the triangle, and above it another geometric form built around a circle, but with a strategically placed dot suggesting an eye and creating an ambiguous fusion and interplay of geometric and organic forms. This effect may be seen in a number of other works from Bauhaus artists of the period, such as Johannes Bertholt’s Eternity (1924) [Fig. 18].

Unlike Itten, Klee at first glance appears to have adapted rather flexibly to the functionalist, constructivist orientation that was becoming Bauhaus policy. But even as he shifted course from expressionism to constructivism, he continued to produce works that wove back and forth between the two. Chinese Picture may be considered a self-portrait which reflects the realities of Klee’s situation and that of the Bauhaus as they underwent a disruptive change of direction. In contrast, in Chinese II densely fills the entire picture plane with forms that have a strong narrative and illustrative tendency. By severing the original painting into two parts, Klee emphasized the character of the first as a self-portrait, with the figure (in other words Klee himself) in Chinese Picture parting from the arty and imaginative

Chinese realm depicted in Chinese II – which the Bauhaus was abandoning as an institution. In the calm, yet sharp and somewhat ironic gaze directed at the viewer by the figure in Chinese Picture we may glimpse the visage of Klee, conscious of Van Gogh’s ideals and their failure, and cooly surveying himself in the midst of the whirlpool of the Bauhaus during its period of transition.

Conclusion

Chinese Picture and Chinese II are works demonstrating that Klee’s interest at this time in Asia and the Orient was not limited to motifs alone, but also extended to method and technique; it might also be said that by severing the two works from one another Klee was expressing his attitude toward his present reality. Current events in the year Klee made these works, 1923, began with the occupation of the Ruhr by French and Belgian forces in January on the pretext that Germany had defaulted on its reparations payments and disruption of the German economy by the »passive resistance« this invited. In Saxony and Thuringia, leftist regimes formed by an alliance of radical Social Democrats and Communists took power in the states of Saxony and Thuringia, but were toppled by the intervention of the central government. And in November, Adolf Hitler staged a failed coup attempt in Munich. The same year, the Bauhaus was criticized by the state assembly of Thuringia, and in August

and September mounted a »Bauhaus Exhibition« that decisively expressed its commitment to a functionalist orientation. Even so, the following year pressure from conservatives forced the Bauhaus to consider closing; in the end, it was relocated to Dessau in 1925. Klee would follow the Bauhaus to Dessau and continue to teach there. The background to the Klee’s two works was thus formed by the dizzying changes taking place in both the internal and external realities surrounding the Bauhaus.

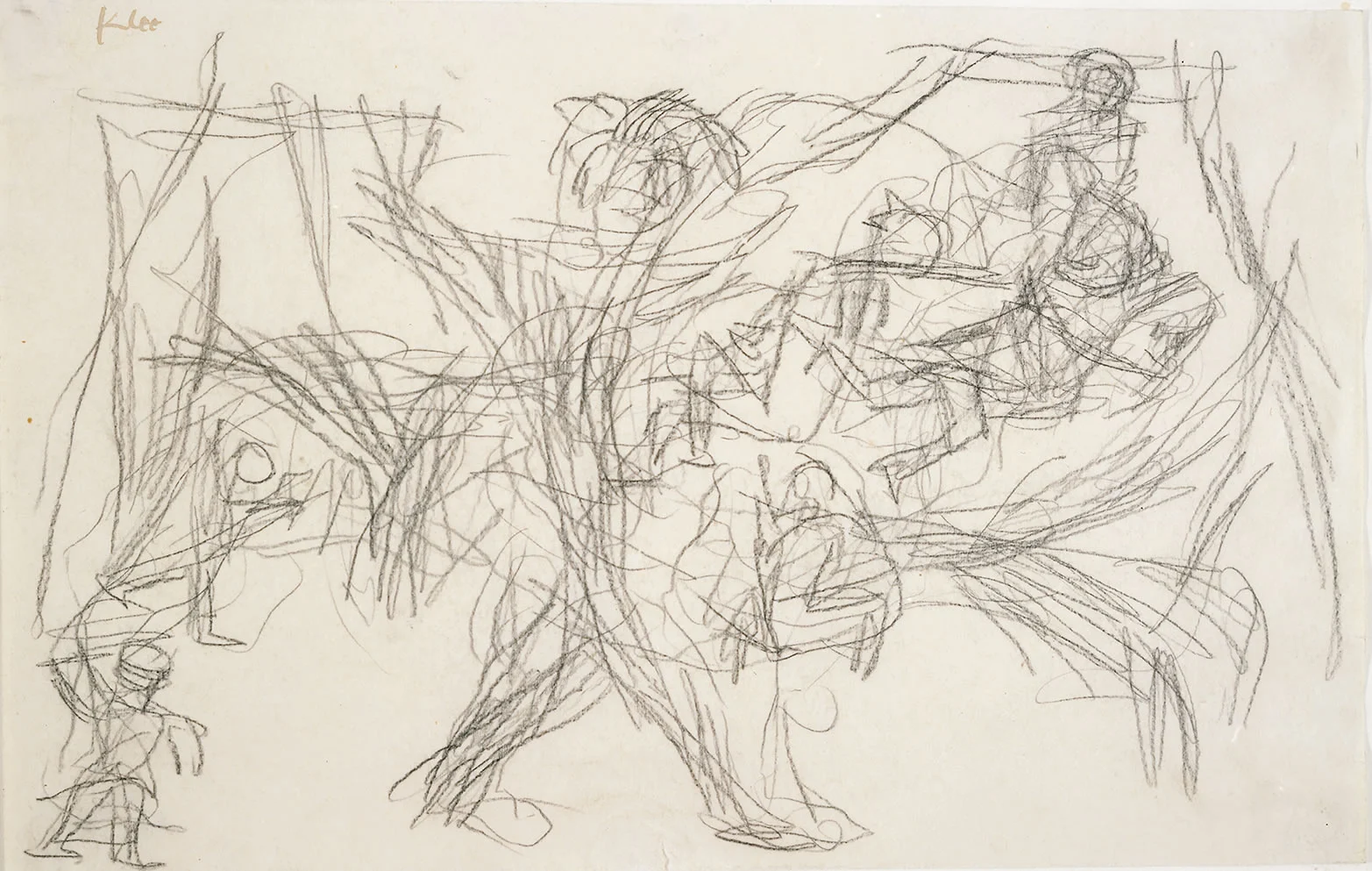

Klee appears to have conceived the left side of the original painting as representing his actual situation and the right as the world of his imagination, and in the end severed them from one another. But this left-right compositional structure would be reunited once again in a work from 1938, Project 1938, 126 [Fig. 19]. Research by Otto Werckmeister has shown that this painting was based on a drawing made in 1933, House Revolution 1933, 94 [Fig. 20] that hints at Nazi violence.54 Following up on this, in 2006, Osamu Okuda has argued that the large central figure in Project is a self-portrait, and that in contrast to the large central figure in House Revolution leading an attack by the figures on the left side of the work against those on the right, in Project Klee has reinterpreted this Nazi activist as a creator of modern art and a modern revolutionary.55

Okuda also draws attention to the presence of a flag in the left-hand side of Project containing more legible figurative forms, seeing it as alluding to the Nazi flag and Nazi propaganda, and expressing the reality in 1938 of Nazi control of Germany. Yet at the same time, he points out that the tormented figures at the right of House Revolution have been transformed in Project into a collection of vivid and vital, albeit fragmentary forms embodying aspirations for the future.56 Moreover, in the catalogue for the 2011 Paul Klee: Art in the Making exhibition at the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto, Okuda relates that Klee’s illness, which before Easter of 1938 had become so severe that the artist was apparently resigned to dying, suddenly abated, and that having weathered this crisis, Klee regained his enthusiasm for the promise of an exhibition in November 1939 commemorating his 60th birthday, which Will Grohmann had secured for him at the Kunsthaus in Zurich – and interprets the central figure in Project as »an allegorical self-portrait of the artist as he strove to make this ambitious exhibition a reality.«57 In Project, two sheets of newsprint have been pasted onto the jute support, joined at the center where the large figure is situated. If, as Okuda suggests, this figure is a self-portrait, then of the pictographic forms scattered over the entire surface of the painting, the more abstract ones on the right represent the future being planned by the artist, while the ones to the left depict the present situation in which he finds himself. At the time of its creation, Klee was once again able to reunite the internal and external realms he was forced to put asunder in 1923. It is entirely possible that Klee recalled Chinese Picture and Chinese II during the process of making Project, considering the flag that is depicted on the left-hand sides of both Chinese Picture and Project, as well as Klee’s awareness of the fact that Chinese characters are pictographic.58 Both 1923 and 1938 were years in which Klee faced a major transition, and responded by producing self-portraits that examined both his internal and external condition – and regardless of whether the end result was a severing or a union, the artist used their production to reaffirm his will to move forward.

Postscript

This paper is a revised and expanded version of an oral presentation delivered on 28 January 2012 at the annual conference of the Eastern Division of the Japan Art History Society meeting at Tokyo University of the Arts. Researcher Osamu Okuda and conservator Patrizia Zeppetella of Zentrum Paul Klee cooperated generously with my research, as did Yuki Kobiyama, curator of the Miyagi Museum of Art, and Jun Ishikawa, curator of the Utsunomiya Museum of Art. I also received valuable comments and advice from the members of the editorial and research committees of the Japan Art History Society. I would like to express my gratitude to all concerned. Research for this paper was supported by a 2011 Grant-in-Aid for Young Researchers (B) from MEXT and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

1 Cf. Noda 2011, pp. 219 - 233.

2 Cf. Delank 1996, p.152.

3 Cf. Baumgartner 2003, p. 106.

4 Cf. Delank 1996, pp. 154 - 159.

5 Cf. Delank 1996, p. 154.

6 Cf. Wagner 2005, p. 66.

7 Cf. Noda 2011, p. 225.

8 Cf. Nakatani 2004, pp. 130 - 131.

9 Cf. Kuß 2011, p. 94.

10 Cf. Noda 2009a; Noda 2009b.

11 Cf. Mitter 2010, p. 152.

12 Cf. Vogelsang 1994, p. 516.

13 Cf. Wagner 2005, p. 70.

14 Cf. Mitter 2010, p. 153.

15 »Liste No. IV. Paul Klee. Meister am Staatlichen Bauhaus in Weimar«, in: Verzeichnis der Bilder für die Ausstellung der Indian Society of Oriental

Art in Calcutta im Oktober 1922, Thüringisches Hauptstaatsarchiv Weimar. »rot violett / gelbgrün, Stufung« (1922/64), »zwei Kioske«»(1922/66), »Herzdame« (1922/63), »Maske« (1922/61), »Schleusen« (1922/60), »Gestirne über den Tempel« (1922, 58), »Gesicht einer Blüte« (1922/57), »Abendsonne« (1922/62), »Palast« (1922/65).

16 Cf. Klee 1979a, p. 885 (an Lily Klee, Gersthofen, 27.10.1917). In Hans Klees Nachlass befindet sich das Buch Gitanjali von Rabindranath Tagore, übers. von Marie Luise Gothein, 9. Aufl., Leipzig 1918.

17 Cf. Noda 2011, p. 222; Noda 2009, p. 120.

18 Kheiri 1921. Noda 2011, pp. 223 - 224.

19 Rudolf/Schröder/Simon-Ritz 2009, p. 141.

20 Cf. Kheiri 1921, pp. 1 - 15.

21 Cf. Grohmann 1954, p. 206.

22 Cf. Klee CR4, p. 140.

23 The fact that Chinese II didn’t turn up before 2009 explains why these pictures are not included in the major study by Wolfgang Kersten and Osamu Okuda from 1995, cf. Kersten / Okuda 1995.

24 It is possible that prior to World War I, Klee had already seen examples of lacquerware or lacquer painting in the personal collections of Jugendstil and Blaue Reiter artists and their associates, or in major exhibitions such as »Japan and the Orient in Art«, mounted in Munich (Cf. Murnau 2011). However, there are no specific references in Klee’s correspondence or diaries confirming that this was the case. A diary entry for 9 January 1917 does contain such a reference: Klee writes of being shown the collection of Bernhard Köhler, remarking on »a couple of fleeing deer embroidered by Frau Niestlé, reminiscent of Chinese art.« (Klee 1964, p. 363)

25 Klee 1979a, p. 315 (an Lily Stumpf, Bern, 5.3.1903)

26 Cf. With 1920, Abb. 1; p. 14.

27 Cf. With 1920, p. 15.

28 Cf. Kümmel 1921, Abb. 86.

29 Cf. Delank 1996, p. 158.

30 Cf. Kümmel 1921, p. 37.

31 Cf. München 1909.

32 Cf. Wahl 1988, p. 279; Noda 2011, p. 226 - 227.

33 Cf. Wahl 1988, p. 20; Delank 1006, p. 136; Baumann 2004, pp. 251 - 254.

34 Cf. Wahl 1988, p. 279.

35 Cf. With 1919; With 1920; With 1922; Noda 2011, p. 227.

36 »Der Mönch am Yangtsekiang«, in: Chinesische Volksmärchen, übers. von Richard Wilhelm, Jena 1914, pp. 281 - 288.

37 Cf. Okuda 2006a, pp. 121 - 122.

38 Cf. Okuda 2006, p. 122; Okuda 2002, p. 21.

39 Cf. Feilfenfeldt 1990, p. 43.

40 Cf. Jeuthe 2009, p. 449.

41 Cf. Paul 2011, pp. 181 - 230.

42 Cf. Jeuthe 2009, p. 461.

43 Cf. Baumann 2004 Auflösung zum Sigel fehlt, p. 58.

44 Cf. Klee 1988, pp. 498, 514.

45 Van-Gogh-Mappe, München 1912; Julius Meier-Graefe, Vincent van Gogh, München 1910.

46 Van Gogh 1914.

47 Cf. Katalog der neuen Staatsgalerie, amtliche Ausgabe, 2. Aufl., München 1921, p. 8.

48 Van Gogh 1958, pp. 66 - 67 (Van Gogh 1914, Vol. 2, pp. 480 - 481).

49 Meier-Graefe 1922.

50 Cf. Okuda 2006a, pp. 121 - 122.

51 Cf. Koudera 2009, p. 171.

52 Cf. Hopfengart 2007, p. 182.

53 Cf. Klee 1979b, p. 37.

54 Cf. Werckmeister 2003.

55 Cf. Okudab, 2006, p. 177.

56 Cf. id.

57 Cf. Okuda 2011, p. 93.

58 For Christmas 1909, Klee was presented by Alexander Eliasberg and his wife with a copy of Hans Heilmann’s Chinese Lyric Poetry [Chinesische Lyrik vom 12. Jahrhundert bis zur Gegenwart, München/Leipzig o.J. (1906)]. In it, Heilmann speaks of the ideographic nature of Chinese characters, and how this unique feature of written Chinese imparts a »painterly and illustrative element« to Chinese poetry (p. XXVI). Klee used a poem from this collection – Wang Seng-Yu’s »Qiu gui yuan« (translated into German as »Die einsame Gattin«, or »The Lonely Wife«) – as material for one of his 1916 »word pictures«, which suggests he took particular note of Heilmann’s interpretation. See Noda 2011, p. 66.

Literatur

Baumgartner 2003

Michael Baumgartner, »Johannes Itten und Paul Klee – Aspekte einer Künstler-Begegnung«, in: Christa Lichtenstern, Christoph Wagner (Hrsg.), Johannes Itten und die Moderne. Beiträge eines wissenschaftlichen Symposiums, Ostfildern-Ruit 2003, S. 100 - 115.

Baumann 2004

Annette Baumann, Paul Klee als Sammler?, Diss., Bern 2004

Delank 1996

Claudia Delank, Das imaginäre Japan in der Kunst. »Japanbilder« vom Jugendstil bis zum Bauhaus, München 1996.

Feilchenfeldt 1990

Walter Feilchenfeldt, »Vincent van Gogh – his collectors and dealers«, in: Vincent van Gogh and the modern movement. 1890 - 1914, Ausst.-Kat. Museum Folkwang, Essen, 11.8.1990 - 4.11.1990; Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam,16.11.1990 - 18.2.1991, pp. 39 - 46.

Van Gogh 1914

Vincent van Gogh, Briefe an seinen Bruder, 2 Bde., Berlin 1914.

Van Gogh 1958

Vincent van Gogh, The complete letters of Vincent van Gogh, Vol. 3, Boston 1958.

Grohmann 1954

Will Grohmann, Paul Klee, Genf/Stuttgart 1954.

Hopfengart 2007

Christine Hopfengart, Theater am Bauhaus«, in: Paul Klee. Überall Theater, Ausst.-Kat. Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern, 28.6. - 14.10.2007, S. 182 - 195.

Jeuthe 2009

Gesa Jeuthe, »›… der armer Vincent!‹ Van Goghs Selbstbildnis von 1888 und der ›Verwertung‹ der ›entarteten‹ Kunst«, in: Uwe Fleckner (Hrsg.), Das verfemte Meisterwerk. Schicksalswege moderner Kunst im »Dritten Reich«, Berlin 2009, S. 445 - 462.

Kersten / Okuda 1995

Wolfgang Kersten and Osamu Okuda, Im Zeichen der Teilung. Die Geschichte zerschnittener Kunst Paul Klees (1883 - 1940). Mit vollständiger Dokumentation, Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 1995.

Kheiri 1921

Sattar M. A. Kheiri, Indische Miniaturen der islamischen Zeit, Berlin [1921]

Klee 1964

The Diaries of Paul Klee 1898 - 1918, ed. Felix Klee, tr. by B. Schneider, R. Y. Zachary and Max Knight, Berkeley/Los Angeles 1964.

Klee 1979a

Paul Klee, Briefe an die Familie 1893 - 1940, Bd.1: 1893 - 1906, Bd. 2: 1907 - 1940, hrsg. von Felix Klee, Köln 1979.

Klee 1979b

Paul Klee, Beiträge zur bildnerischen Formlehre, hrsg. von Jürgen Glaesemer, Basel/Stuttgart 1979.

Klee 1988

Paul Klee, Tagebücher 1898 - 1918, textkritische Neuedition, hrsg. von der Paul-Klee-Stiftung, Kunstmuseum Bern, bearb. von Wolfgang Kersten, Stuttgart und Teufen 1988.

Klee CR4

Catalogue raisonné Paul Klee, Bd. 4, 1923 - 1926, hrsg. von der Paul-Klee-Stiftung, Kunstmuseum Bern, Bern 2000.

Koudera 2009

Koudera Tsukasa, Van Gogh: Struggle of nature and religion, Tokyo 2009.

Kümmel 1921

Otto Kümmel, Die Kunst Ostasiens, Berlin 1921.

Kuß 2011

Susanne Kuß, »Chinas Völkerbundspolitik 1920-1930: Der Kampf um die Aufhebung der ungleichen Verträge«, in: Katja Levy (Hg.), Deutsch-chinesische Beziehungen, München 2011, S. 92 - 105.

Meier-Graefe 1922

Julius Meier-Graefe, Vincent, München 1922.

Mitter 2010

Partha Mitter, »Bauhaus in Kalkutta«, in: Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin (Hrsg.), Bauhaus global. Gesammelte Beiträge der Konferenz bauhaus global vom 21. bis 26. September 2009, Berlin 2010, S. 149 - 158.

München 1909

Japan und Ostasien in der Kunst, Offizieller Katalog der Ausstellung, München 1909.

Murnau 2011

»...diese zärtlichen, geistvollen Phantasien...« Die Maler des »Blauen Reiter« und Japan, Schlossmuseum Murnau, 21.07. - 06.11.2011.

Nakatani 2004

Tadashi Nakatani, »Wilson and Japan: The Shandong Question at Paris Peace Conference, 1919«, in: The Doshisha Hogaku (The Doshisha law review), Vol. 56, Nr. 2, 2004, pp.79 - 166.

Noda 2009a

Yubii Noda, Paul Klees Schriftbilder: Blick auf Asien, den Orient und die Musik, Tokyo 2009.

Noda 2009b

Yubii Noda, »Die Beziehung zwischen Paul Klee und ›Ostasien‹ bis zum Entstehen der ›Schriftbilder‹ im Jahre 1916« (Jap.), in: Paul Klee and East Asia, Ausst.-Kat. Chiba City Museum of Art, 16.5. - 21.6.2009; Shizuoka Prefectural Museum of Art, 14.7. - 30.8.2009; Yokosuka Museum of Art, 5.9. - 18.10.2009, pp. 65 - 85; 157 - 158.

Noda 2011

Yubii Noda, »Paul Klees Verhältnis zu Asien und Orient im Spiegel seiner Lektüre zwischen 1919 und 1924« (Jap.), in: Bigaku-Bijutushi Ronshu, Seijo University, Nr. 19, März 2011, S. 219 - 233.

Okuda 2006a

Osamu Okuda, »16 Buddhistischer Mönch«, in: Christine Hopfengart (Konzeption und Red.), Eva

Wiederkehr Sladeczek (Red.), Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern (Hrsg.), Paul Klee. Handpuppen, Ostfildern 2006, S. 121 - 122.

Okuda 2006b

Osamu Okuda, »Bildtotalität und zerstörerischer Werkprozess bei Paul Klee«, in: Reto Sorg und Stefan Bodo Würffel (Hrsg.), Totalität und Zerfall im Kunstwerk der Moderne, München 2006, S. 163 - 182.

Okuda 2011

Osamu Okuda, »Paul Klees Atelier in Bern 1934 - 1940«, in: Paul Klee. Art in the making 1883 - 1940, Ausst.-Kat. The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto, 12.3. - 15.5.2011; The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, 31.5. - 31.7.2011, S. 40 - 47.

Paul 2011

Barbara Paul, Hugo von Tschudi und die moderne französische Kunst im deutschen Kaiserreich, Mainz, 1993.

Rudolf/Schröder/Simon-Ritz 2009

Sylvelin Rudolf, Jana Schröder, Frank Simon-Ritz, »Die Bibliothek des Staatlichen Bauhauses in Weimar«, in: Michael Siebenbrodt, Frank Simon-Ritz (Hrsg.), Die Bauhaus-Bibliothek. Versuch einer Rekonstruktion, Weimar 2009, S. 128 - 169.

Vogelsang 1994

Bernd Vogelsang, »Chronologie des Weimarer Bauhauses. 1919 - 1925«, in: Das frühe Bauhaus und Johannes Itten, Ausst.-Kat. Kunstsammlung zu Weimar, 16.9. - 13.11.1994; Bauhaus-Archiv, Museum für Gestaltung, Berlin, 27.11.1994 - 29.1.1995; Kunstmuseum Bern, 17.2. - 7.5.1995, S. 511 - 522.

Wagner 2005

Christoph Wagner, »Zwischen Lebensreform und Esoterik: Johannes Ittens Weg ans Bauhaus in Weimar«, in: Johannes Itten, Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee. Das Bauhaus und die Esoterik, Ausst.-Kat. Gustav-Lübcke-Museum, Hamm, 28.8.2005 - 8.1.2006; Museum im Kulturspeicher, Würzburg, 22.1. - 22.4.2006, S. 65 - 77.

Wahl 1988

Volker Wahl, Jena als Kunststadt. Begegnungen mit der modernen Kunst in der thüringischen Universitätsstadt zwischen 1900 und 1933, Leipzig 1988.

Werckmeister 2003

Otto Karl Werckmeister, »Körperfigur und Kunstfigur in Klees Zeichnungen von 1933«, in: Paul Klee 1933, Ausst.-Kat. Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, München, 8.2. - 4.5.2003; Kunstmuseum Bern, 4.6. - 17.8.2003; Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt/M., 18.9. - 30.11.2003; Hamburger Kunsthalle, 11.12.2003 - 7.3.2004, S. 217 - 227.

With 1919

Karl With, Buddhistische Plastik in Japan, 2 Bde., Wien 1919.

With 1920

Karl With, Asiatische Monumental-Plastik, Berlin [1920].

With 1920

Karl With, Java. Buddhistische und brahmanische Architektur und Plastik auf Java, Hagen 1922